Ariana Grande Is Once Again Cosplaying As Another Race. We Should Probably Talk About It

By Stacy Lee Kong

Image: instagram.com/arianagrande

Content warning: this newsletter contains references to sexual assault and anti-Asian violence.

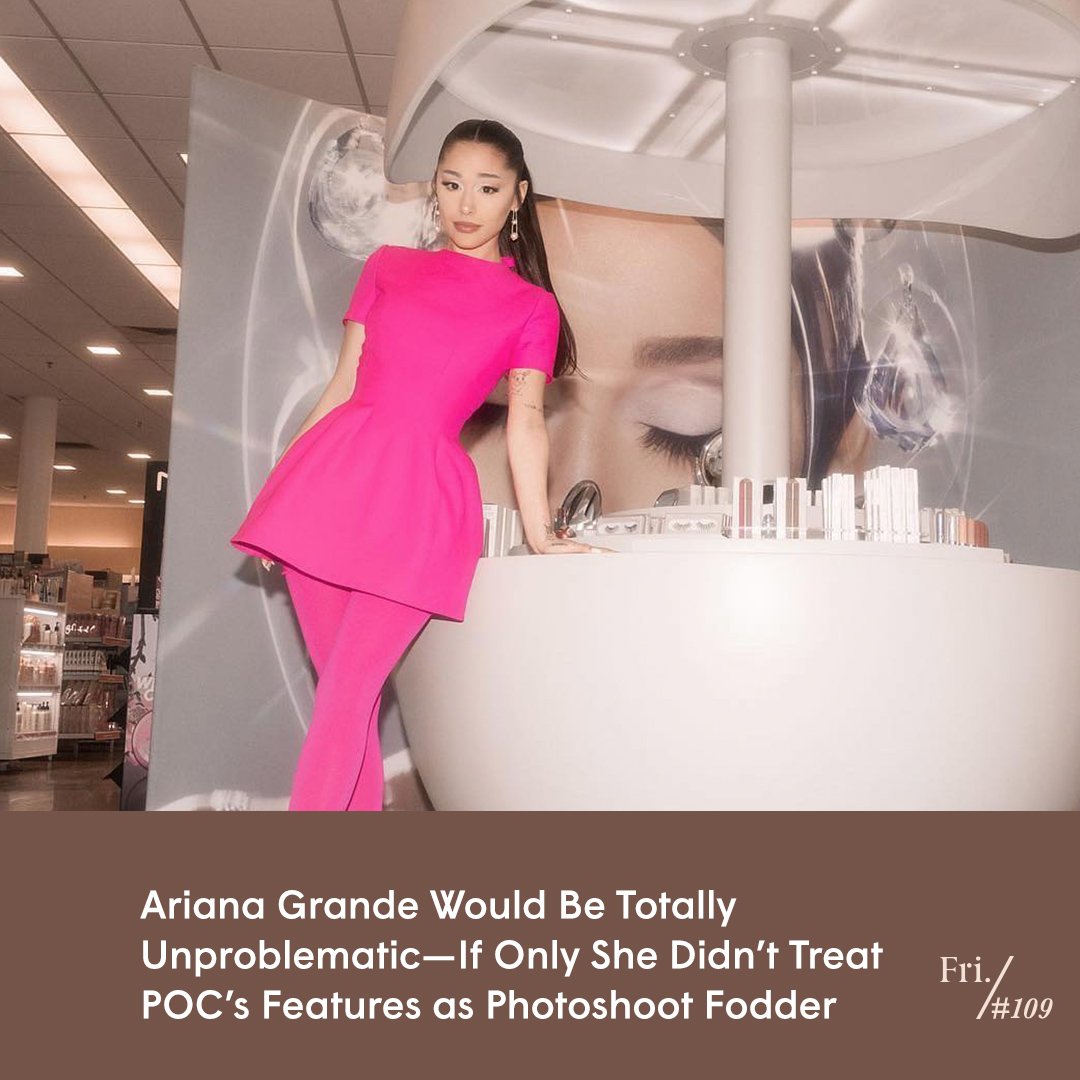

When I first saw Ariana Grande’s most recent Instagram photo, I didn’t even realize it was her. I honestly thought I was looking at a K-beauty influencer or K-pop star. And no wonder; in the photo, Grande is posted up at a beauty counter to celebrate her R.E.M. Beauty makeup line launching at Ulta, wearing an all-pink outfit, her trademark high pony—and a makeup look that was giving, well, yellowface. The angle of her winged liner and the way her eyeshadow is applied makes it look like she has monolids, while the editing of the photo (or maybe the flash) makes her skin appear much lighter than her usual questionably dark tan. The overall effect is not “Italian American, half Sicilian and half Abruzzese” as she tweeted in 2011, but rather the exact same type of racial cosplay that we are currently seeing all over TikTok and Instagram.

In Ariana Grande's most recent Instagram post (left) she appears to have monolids and lighter skin than in other recent photos (right). (Images: instagram.com/arianagrande)

… Which is why I was kind of surprised to see little to no news coverage about these images. To be fair, the last time Grande posted photos where she appeared to have monolid eyes and lighter-than-usual skin (back in December), there wasn’t much coverage, either. What did exist was relegated to tabloids, with just a few mainstream publications wading into the debate—and even then, they made sure to note that not everyone saw a problem with her look. As Cosmopolitan UK pointed out at the time, “others have jumped to her defence, with one fan saying on Twitter that the comments were from non-Asian people but that many Asians and South East Asians didn't notice. While another pointed out that Ariana respects Asian cultures and cultures around the world. Others have also said that her skin would be lighter in winter, or could be down to the camera flash.” But at least that was something. This time around? Crickets.

Maybe these outlets think conversations about Asianfishing, or yellowface, or whatever we’re calling it these days, are played out. Or maybe they think the reaction they'd get from Grande’s stans isn’t worth it. (Which… fair.) But I do think these images are worth talking about because, much like when we all spent a lot of time discussing Grande’s Blackfishing, her aesthetic choices illuminate problematic dynamics in our society that are, unfortunately, extremely timely. (If you missed the Blackfishing convo, it's a term coined by Toronto cultural critic Wanna Thompson for white women who cosplay as Black on the internet; this is a good breakdown of how Grande did it.)

Pretending to be Asian—on the internet and otherwise—is a whole thing

Grande and her makeup artists didn’t land on this look by chance. Internet subcultures that basically amount to Asian fetishism have existed for years, if not decades. Anime and K-pop fans are likely already familiar with the derogatory terms “weaboo” and “Koreaboo,” which are sometimes used to refer to people who are so obsessed with the cultures of Japan and Korea respectively that they pretend they actually are Japanese or Korean, discarding their own ethnic and cultural backgrounds in favour of performing an appropriated version of Asianness on the internet. More recently, a trend has emerged among YouTubers, Instagrammers and TikTokers to use makeup, filters and camera angles to mimic stereotypical East Asian features. Worse, they’re often completing the look by dressing in schoolgirl uniforms or other youthful clothing and posing sexily, which plays into both a weird internet obsession with portraying Japanese culture as kinky and hypersexual, and existing stereotypes about Asian women’s submissiveness and sexual availability. (Grande’s overall aesthetic, which Vice has called “deceptively childlike,” feels especially icky in this context.)

This happens offline, too, of course. Oli London, a white British internet personality, has undergone several plastic surgery procedures to look more like BTS’s Jimin and even goes so far as to identify as “transracial Korean,” which is obviously not a thing. (They were a huge fan of Grande’s December photos, btw.) And remember the fox eye makeup trend that was everywhere in summer ’20? In addition to the actual makeup, which involved drawing on a straight brow and using eyeshadow to create the illusion of narrower, upturned eyes, influencers who tried it also posted photos in a very particular pose: fingers pulling their eyes back toward their templates to exaggerate the slanted effect. It’s one I know you’ve seen before, though in a slightly different context. As writer Sara Li argued in Teen Vogue, “it is not accidental that mainstream beauty standards would, yet again, steal select features from another culture, when that very same feature has been weaponized against its origin community in the past.”

Or, we can go back even further. There is a very long history of white actors wearing makeup, prosthetics and costumes to not just mimic stereotypically East Asian features but also to embody an offensive—and specifically American—idea of Asianness that doesn’t authentically reflect the region's cultural diversity. And I’m not just talking about historical Sinophobic characters like Fu Manchu, the original model minority, Charlie Chan, or WW2-era anti-Japanese cartoons; in the 2010s alone, Sherlock Holmes, Cloud Atlas and How I Met Your Mother used actual yellowface, while Aloha, Dr. Strange and Ghost in the Shell, which all cast white women to play Asian characters.

Do we really still have to talk about treating other ethnicities’ physical features as costumes?

Grande has never publicly commented on any of her racial cosplay adventures, but her fans are quick to offer up excuses: that this is solely an aesthetic choice, that it wasn’t an intentional slight, that characterizing small or slanted eyes as Asian is racist in itself because people from any ethnicity can have that particular eye shape. That last part is true, which is why it’s wrong (and anti-Black) when commenters lob the term Asianfishing at Black creators who naturally have monolids or almond-shaped eyes. But in general, this is a bad-faith argument. It would be extremely silly to pretend that this eye shape isn’t prominent among East Asian people, and more importantly, that Western society hasn’t spent generations mocking all Asians for it.

As Monica Kim wrote last year in a powerful essay about learning to love her monolids, “technically known as an ‘epicanthic fold,’ colloquially as monolids, and ignorantly as ‘Asian eyes,’ the characteristic is perhaps most recognizable as a defining feature of racist caricatures, both from the turn of the century and now, in which small, slanted eyes draw focus: One line dragged sharply up, one line beneath it, and one dash for the beady pupil. In America, people tend to forget the breadth of the Asian continent: Korea, Japan, and China, yes, but Thailand, Malaysia, India, Bangladesh, and other countries as well, filled with single lids and double lids, eyes of brown and black and hazel. Yet the monolid has come to symbolize a vague notion of Asianness, reducing billions of people to three simple strokes.”

This is not really about eyeliner, the same way conversations about Grande's Blackfishing aren’t about self-tanner. It’s about how dehumanizing it is when young, mostly white women separate racialized peoples’ physical characteristics from our ethnicities so they can 'try on' the parts of us they find most aesthetically pleasing. It’s about taking the very same characteristics that Western society said made racialized people different, undesirable and unworthy and repackaging them as beautiful—as long as they’re not on an actual person of colour. And it’s about how this just keeps happening. We’ve had this conversation many (many) times before; Black, South Asian, Indigenous and East Asian features are regularly appropriated for aesthetics, clout and financial gain by people who don’t feel any corresponding responsibility to engage with the oppression that disproportionately affects these groups. Worse, they’ll have us believe it doesn’t matter, that it's just makeup, when actually it’s hypocrisy, callousness and racism.

This is especially troubling considering the ongoing incidents of anti-Asian hate

Earlier this week, Panthea Lee published an excellent, though difficult to read, article in The Nation about the direct line between American imperialism in Asian countries and the current wave of anti-Asian violence, which often targets women. She cites the U.S. military’s practice of “registering” Filipina sex workers during the America-Philippine war in the late 1800s, “test[ing] them for venereal diseases, and tag[ging] them, like pets, reinforcing their status as less than human,” a practice that “[laid] the foundation for the region’s notorious sex entertainment and trafficking industries.” During the Korean War in the 1950s, the U.S. military introduced R&R, a program intended to provide soldiers with rest and recuperation by sending them to Japan to take advantage of that country's “comfort stations,” which were staffed by sex slaves. Lee argues that this decades-long practice of offering up Asian women to sate American men’s needs indelibly linked Asian women with sexual availability and servitude in the American imagination, and that this is a key factor in the type of violence Asian women in America face today.

Weirdly, there is an eye-shape connection here, too. As Kim explains in her essay, ssanguhpul, the double-eyelid surgery that accounts for 23% of all plastic surgeries in Korea, is also a legacy of the American military. “We did not want to look white. It wasn't as simple as that,” she writes. “Yet the further back I look, the harder it is to ignore the groundwork that has been laid—by the American military surgeon who came to postwar Korea and began converting what he called ‘expressionless eye[s] sneaking a peep through a slit;’ by the U.S. forces who arrived before that and hoped to reshape the country in their image, leaving scars so deeply internalized we are not even aware of them.”

Ariana Grande wearing makeup that makes her eyes appear slanted is obviously not the same thing as the type of sexist, racist violence Lee is describing or even the imperialistic redesigning of Korean beauty ideals that the military surgeon sparked. But it’s hard not to think about how these different types of dehumanization inform one another. After all, aren’t they all about taking the bits of Asian women that white people find most useful, then metaphorically—or literally—discarding the rest?

And Did You Hear About…

Charli XCX’s villain era—and Nylon’s smart analysis of this pop music rite of passage, which everyone from Taylor Swift to Lil Nas X to Madonna has experimented with at some point in their careers.

The fans that DM their fave celebrities about the quotidian details of their daily lives.

Harper’s Bazaar’s excellent article on diverse casting and costuming in several recent historical epics, including Bridgerton and The Gilded Age.

How the linguistic meaning of LOL has evolved.

This Twitter round-up of the best magazine covers of all time.

Thank you for reading this week’s newsletter! Still looking for intersectional pop culture analysis? Here are a few ways to get more Friday:

💫 Join Club Friday, our new membership program. Members get exclusive Q&As with pop culture experts, early access to Friday merch and deals and discounts from like-minded brands.

💫 If you’d like to make a one-time donation toward the cost of creating Friday Things, you can donate through Ko-Fi.

💫 Follow Friday on social media. We’re on Instagram, Twitter, Facebook and even (occasionally) TikTok.