Billie Eilish's New Look Is Grown and Sexy, And I Feel Conflicted About It

By Stacy Lee Kong

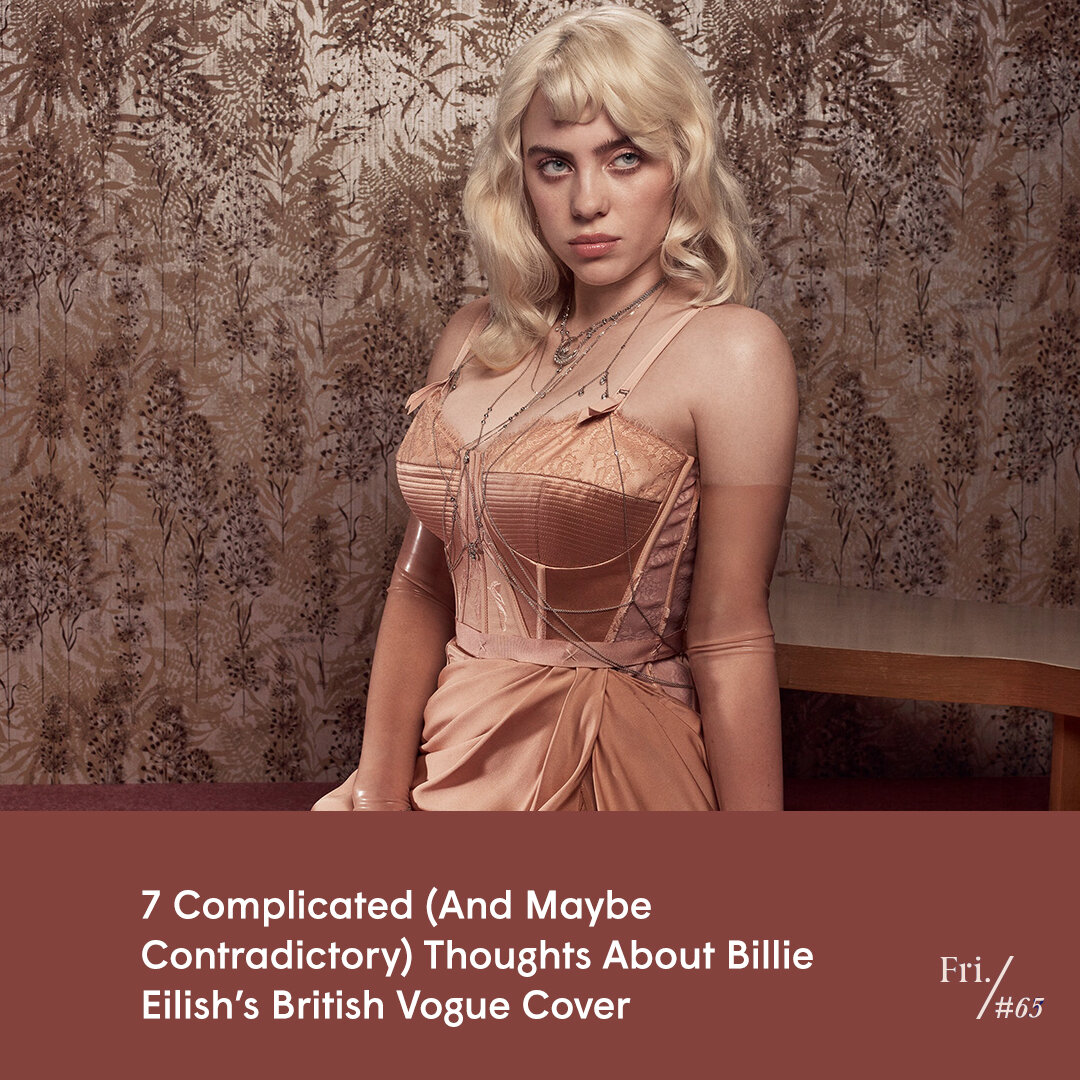

Image: Craig McDean for British Vogue

Content warning: This newsletter contains references to body image and appearance.

Three Mondays ago, Billie Eilish posted a photo of herself with blonde hair, a drastically different outfit than her usual oversized style—pearls, a tight-fitting Gucci logo cardigan—and an excited but vague caption: “things are comingggg.”

“Things” seemed to refer to the next ‘era’ in her career, which she kicked off with the release of her next single, “Your Power,” two Mondays ago. Though she’s still singing in her signature whispery, emo-pop style, the lyrics feel more complex than those on her Grammy-winning debut album, 2019’s When We All Fall Asleep, Where Do We Go? As the Guardian puts it, “the themes of When We All Fall Asleep offered teenage angst skilfully [sic] whipped up into gothic melodrama: jealousy and heartbreak, self-loathing, worrying about drugs. Your Power’s subject matter deals with the considerably darker topic of sexual abuse, coercion and control: an older man, who the lyrics suggest is either a musician or actor—‘Will you only feel bad if it turns out they kill your contract?’—preying on a young woman, a situation that’s ‘ruined her in a year.’”

Then, this past Monday, the latest issue of British Vogue dropped and it was suddenly really clear: this new era isn’t just about sonic maturity, it’s also about aesthetic maturity. At 19, she’s ready for the world to see her as an adult.

But while she looks beautiful in the British Vogue photos, I’m still conflicted about them—though maybe not for the reasons you might expect.

I wasn’t sure how to talk about Eilish’s ‘transformation’ at first

When I posted about this shoot on Friday Things’ IG Stories, I only said that I thought she looked great, which she does. Her blonde hair is super-flattering, her makeup is an understated glam and she’s wearing pin-up-inspired lingerie in shades of dusky pink, taupe and black that’s beautiful but still edgy. (The New York Times describes it as, “a style more domme than deb: pink Gucci corset and skirt over Agent Provocateur skivvies, accessorized with latex gloves and leggings.”)

What I didn’t say—what I wasn’t sure how to talk about—was what it meant for this cover to be so different from her usual style. Unlike the 90s and early 2000s when criticizing young women for their sartorial choices were de rigueur, it’s no longer acceptable to disparage their clothing choices, or their bodies. This is amazing, obviously, but it does sometimes mean that any critique or questioning can be interpreted as shaming, which is obviously not my goal.

But I do have questions, because this lingerie-clad cover feels very disconnected from what she’s worn, and more importantly, said before. In the past, she’s talked about not wanting to be body-shamed, telling Vogue Australia in 2019, “What I like about dressing like I'm 800 sizes bigger than I am is, it kind of gives nobody the opportunity to judge what your body looks like. I don't want to give anyone the excuse of judging… I want layers and layers and layers. I want to be mysterious. You don't know what's underneath; you don't know what's on top.”

Earlier that year, she appeared in a Calvin Klein ad where she expressed similar feelings, saying, “Nobody can have an opinion because they haven’t seen what’s underneath, you know? Nobody can be like, 'She’s slim-thick,' 'She’s not slim-thick,' 'She’s got a flat ass,' 'She got a fat ass.' Nobody can say any of that because they don’t know."

For the record, Eilish's frustration is totally justified. As recently as October, a photo of her wearing a tight tank top went viral and people fell over themselves to either shame her for the size and shape of her body, or praise her for being "brave" enough to... be seen in that body, I guess? The scrutiny even inspired her to create a short film, Not My Responsibility, for her 2020 tour, which she later posted online. In it, she strips down to her bra while delivering a monologue about the public’s obsession with her body.

But when I read the British Vogue article, I wasn’t sure that her feelings about receiving this kind of attention had changed. Especially because she revealed her inspiration for the shoot was partially about exploring the beauty of corsets, and partially about controlling her body. “If I’m honest with you, I hate my stomach, and that’s why,” she told writer Laura Snapes.

But after thinking about it for days now, I’ve decided: this is totally a ‘many things can be true’ situation

It wasn’t until I saw this tweet that I was able to better articulate what was I was thinking.

As New York University doctoral candidate Wendi Muse pointed out on May 2, “the ‘girl to woman’ transition in Hollywood and the music industry always involves hypersexualization, and people should consider what that means and why men rarely, if ever, have to make this kind of transition to be taken seriously as artists… (And, yes, I recognize that some women choose to do this, but these choices are not made in a vacuum. We also must consider who ends up cashing out the most as this process occurs, then add to it the weird ‘countdown to 18’ culture and the like. It's grooming in public).”

According to British Vogue editor-in-chief Edward Enninful, “she came to Vogue with an idea. What if, she wondered, she wanted to show more of her body for the first time in a fashion story? What if she wanted to play with corsetry and revel in the aesthetic of the mid-20th century pin-ups she’s always loved? It was time, she said, for something new.”

So yes, the inspiration for this shoot—"a ‘classic, old-timey pin-up’ look inspired by Betty Brosmer, Horst’s illusionist beauty shots and the stockinged models of Elmer Batters”—was Eilish’s. And if she's trying to signal that she's more comfortable with her body now, and more prepared for people to scrutinize it, well, that’s what we want, right? It’s not only completely okay for young women to become more comfortable in their bodies, and their own their sexuality, it's actually desirable.

It's just impossible to divorce her decisions from a larger system that demands young women perform sexuality for public consumption to signal their ascension into adulthood.

In a way, Eilish’s new look has arrived right on schedule

I think it’s worth thinking deeply about these images because they’re bringing up issues that aren't isolated in a single shoot. The cover is being positioned as an introduction to a new stage not just in Eilish’s career, but also her development as a person. That’s not unusual; pop stars have used aesthetic changes to signal new eras from time—hello, Madonna? But as Muse points out, Eilish is also playing into a larger, and far more problematic, tradition of using sexual availability as a signifier for maturity.

This is often something that happens to young women. It has been common to see countdowns to young celebrities’ 18th birthdays, at which point they’d be ‘legal’ and adult men would no longer be committing statutory rape if they had sex with them (🤮). And to be clear, these are literal sites with clocks that calculated the number of minutes left until men—because yes, it was almost always men—could legally have sex with Britney Spears, the Olsen twins, Natalie Portman, Hilary Duff and Emma Watson, among others. Worse, it would also then be legal to compile sexual images of these young women, and the same men who were watching the clock were also waiting to form communities where they could share them.

“Mainstream media supported the trend, too,” British journalist Yomi Adegoke pointed out in 2019. “‘Hot, Ready and Legal!’ Rolling Stone’s August 2004 cover exclaimed about a then 18-year-old Lindsay Lohan, pictured in a strappy satin top. ‘Kendall Jenner—53 Days until she turns 18. Not that we’re counting,’ celebrity-gossip site TMZ captioned an image of her, wearing a bikini top and tugging at a pair of tiny shorts. ‘To all those wondering, Kendall Jenner turns 18 in 52 days,’ Hollywood Life wrote below the same image a day later.” Watson has also spoken about photographers for a British tabloid following her on her 18th birthday to take upskirt photos, which they could legally publish since she was now technically an adult.

And sometimes young women even end up participating in their own sexualization. I feel like we can all rhyme off a long list of young women who have debuted their own new aesthetics, taken on more mature projects or made provocative posts on social media to signal maturity: Spears, Selena Gomez, Miley Cyrus, Rihanna, Demi Lovato, Millie Bobby Brown, Amanda Bynes, Lindsay Lohan… I mean, this year, Bhad Bhabie, the teenager who became famous for telling Dr. Phil to “cash me outside” started an OnlyFans account for her 18th birthday.

And you know, I get it. At 18, I also wanted to be seen as an adult, and probably made questionable decisions because of that—and I didn’t have producers and photographers and agents and casting directors also encouraging me to sex up my look for professional success.

She may not have as much agency as she thinks she does

To be clear, when young women participate in image-making that objectifies them, as those young women and, I’d argue, Eilish have all done, it doesn’t mean they are complicit in, or deserve, sexualization, only that it’s complicated—especially since their agency is not the only force at play.

I think this is why I—and a lot of people in Friday Things’ DMs—saw a crystal-clear connection between the British Vogue cover and Tavi Gevinson’s brilliant essay about Framing Britney Spears for The Cut earlier this year. Gevinson’s thesis, bolstered by her own experience as a teenager moving through adult spaces, is that even when young women have power, access and visibility, they’re still subject to society’s existing power dynamics. “I can see why a viewer would find relief in concluding that Spears was always in complete control. But it is absurd to discuss her image from that time as though there was not an apparatus behind it, as though she existed in a vacuum where she was figuring out her sexuality on her own terms, rather than in an economy where young women’s sexuality is rapidly commodified until they are old enough to be discarded,” she writes. Simply put, “Spears’s agency may have been compromised by her age, the stakes of wealth and fame, or the influence of the adults around her.”

For all that I see and appreciate Eilish's agency, I don't think there are big enough differences between today's entertainment industry and the one Spears was navigating 20 years ago, or the one Gevinson was navigating even more recently, to believe that her analysis doesn't apply here too. And even if Eilish feels like she was in total control of this shoot now, there’s no guarantee that she’ll still feel like that later. After all, last year, Gomez told Allure that she’d felt pressure to be overtly sexual in her past music videos. “There was pressure to seem more adult on my album, Revival. [I felt] the need to show skin... I really don't think I was [that] person,” she said. And in 2018, when Portman told an interviewer she’d been “confused” by a 1999 magazine cover that featured Jessica Simpson in a bikini while the singer proclaimed her virginity in the interview inside, Simpson responded by reminding her that “we both know our image is not totally in our control at all times, and that the industry we work in often tries to define us and box us in,” an insight that may have taken time for her to be able to articulate.

However! Miss me with any BS about Billie no longer being a good role model

Wearing lingerie, embracing her body, sending the message that she’s a sexual being—none of that is wrong. What’s more, it’s not her job to protect kids from images or ideas that their parents find objectionable. Cardi B can have the final word on this entire idea, okay?

Weirdly, we don’t expect young men to objectify themselves to prove they’re adults 🙄

Teens of all genders want to look and feel like adults—but somehow, young men’s bodies aren’t up for consumption in the same way. Take Zac Efron. I remember reading a 2009 GQ profile of Zac Efron and thinking, “Oh, this is his ‘I’m not a kid anymore’ article.” In addition to being a striking look into early oughts-era ideas about masculinity (“guyliner” and false eyelashes = a no), it’s also wild to see that, while the entire piece explores the tension between youth and maturity, he’s never sexualized. He’s photographed in a suit, of course.

Or here’s a more recent example. Earlier this year, Stranger Things’ Caleb McLaughlin was featured in Flaunt magazine as part of the promotional tour for Concrete Cowboys and everyone who I saw share it talked about how grown-up he looked. But in each of the photos, he just had a moustache and was wearing really cool outfits. Like Efron, we could understand him as adult without also sexualizing him.

Ideally, we’d exist in a world where people’s bodies aren’t news

In her interview, Eilish argues that “showing your body and showing your skin—or not—should not take any respect away from you,” and she’s 100% right. The point I’m trying to make here is not that there’s anything wrong with her look, or her body. In fact, as I’ve written before, I’m excited for the day when no one’s body is news.

But in the meantime, I don’t think we have the luxury of taking these images at face value and ignoring the context in which they’re created. So yeah, we do have to consider what it means when a young woman still opts to strip down to signal that she’s growing up.

And Did You Hear About…

This op-ed that links Josh Duggar’s arrest on child pornography charges (and two other recent scandals) to wider issues within evangelical Christianity.

Toronto philanthropist Suzanne Rogers and her husband Edward, the chairman of Rogers Communications and the Toronto Blue Jays, palling around with noted white supremacist Donald Trump last weekend.

The oral history of the Dawson crying gif.

This smart piece on the problem with expecting “authenticity” from racialized chefs and food entrepreneurs.

Slate’s thoughtful take on race in Netflix’s new fantasy series Shadow and Bone, and why it’s more like Bridgerton than writer Elyse Martin would prefer.