After a Week of Skinny Propaganda, I'm Thinking A LOT About Hunger as Social Control

By Stacy Lee Kong

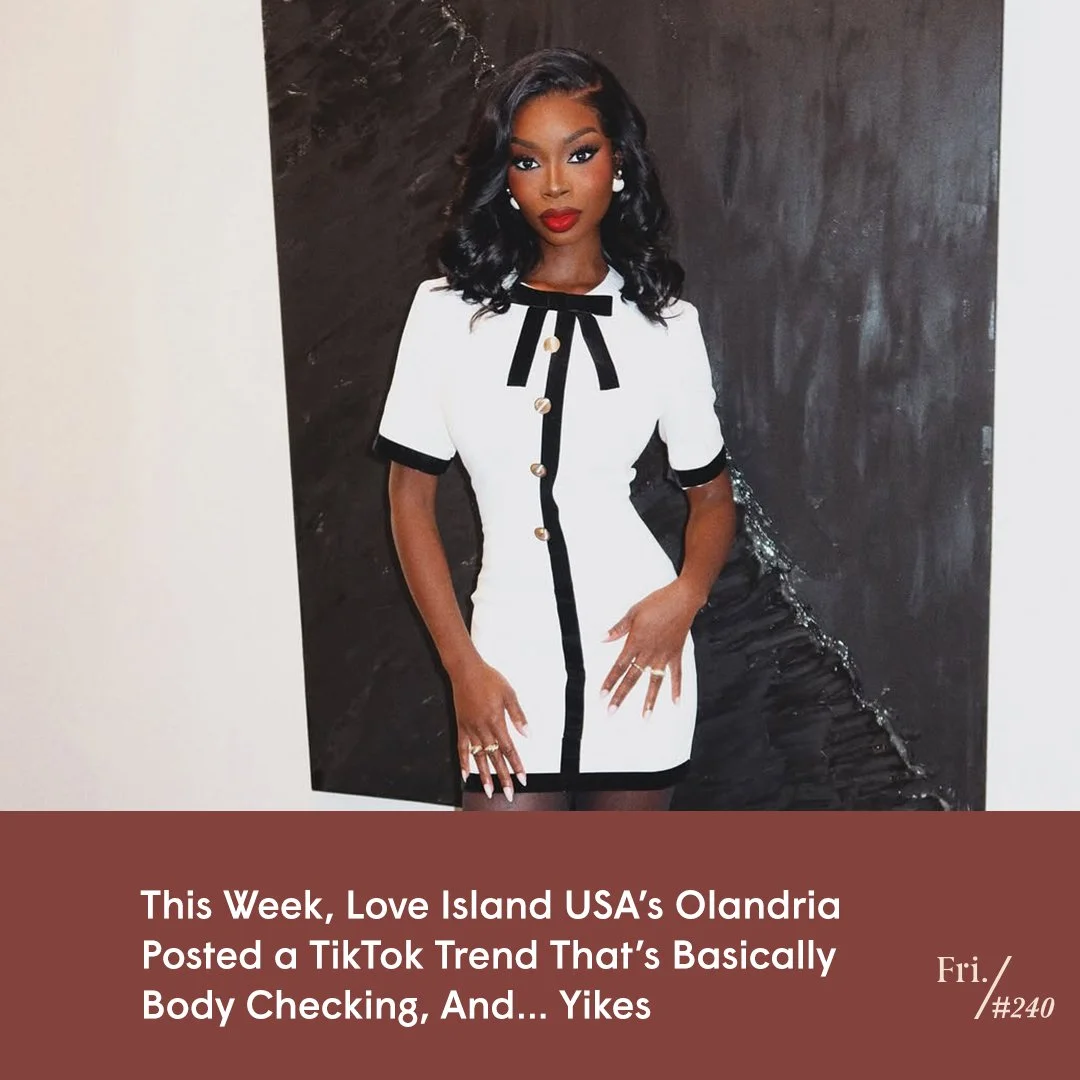

Image: instagram.com/x_olandria

So… The girls are getting very skinny again. This isn’t new, I know, but this week, it has been very, very noticeable: Love Island USA star Olandria Carthen started (or maybe just popularized? I’m unclear) a TikTok challenge that involves putting sunglasses around your waist to show off how skinny you are. Tradwife influencer Nara Smith posted a photo of herself holding her two-week-old baby while wearing low-rise pants and a cropped sweater, putting her flat stomach on full display. And, my TikTok algorithm is suddenly serving up a seemingly endless stream of videos from a body positivity advocate who I quite like, but usually don’t see on that app. Weirdly, I’m only seeing content about her recovery from a BBL, tummy tuck and arm lift.

OLANDRIA THIS WAISTTTT pic.twitter.com/cgIwlJGjhU

— niah ❤︎ (@kordenas) October 25, 2025

I strongly believe that women can do whatever they want with their bodies, obviously, but I also find it pretty distressing to see all of these reminders that thin is really, really in again. Some of that is personal; back in 2021, I reflected on being bombarded with dieting advice and images of beautiful women who were significantly smaller than I was, but still somehow ‘too fat,’ particularly from my early teens to early 20s. (Ironically, in a newsletter about how diet culture had morphed, but hadn’t disappeared.) There was so much that was damaging about that time. It wasn’t just the constant visual feedback about thinness being the ideal, it was also the way entertainment and gossip publications wrote about young female celebrities, nit-picking their bodies, highlighting their so-called imperfections and objectifying them as sexual objects, but only as long as they were acceptably small. And it was all very convincing! Even though I knew it was wrong for adults to talk about girls and young women that way, and I believed in the ideas that any type of body could be beautiful and every type of body was valuable and deserving of love and care, I still wanted to have the ‘right’ body. I still wanted to be beautiful and desirable, and I suspected that the only way to do that was to have a completely different body than my own. In short: that was a terrible time, and I don’t want to experience it again, much less subject younger women to the same B.S.

But, beyond my personal feelings on the demise of body positivity, I’ve also been thinking about how a cultural and aesthetic return to thinness means accepting a state of hunger, and what that means from a political perspective. Earlier this week, journalist, author and academic Stacey Patton broke down the U.S. government shutdown, which could lead to millions of people losing access to the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, or SNAP. Her argument was that cancelling a program that helps 1 in 8 Americans access food every month is a deliberate policy intended to implement social control. “Hunger doesn’t just weaken the body, it rewires the mind for obedience,” she wrote. “And that’s exactly the point. A starving population doesn’t resist. It obeys.”

Who benefits from (mostly) women becoming their physically weakest and least imposing? Never women!

Patton is talking about the American public in general, and we’ll get back to that, but I do want to think a little bit about what it means to promote an aesthetic that keeps women, specifically, in a state of hunger. According to the Australian National Eating Disorders Collaboration, “we know that brain activity is affected by even modest dieting. When a person is malnourished, their brain is not adequately fuelled; they struggle to make decisions, solve problems and regulate their emotions. Restricted eating, malnourishment and excessive weight loss can lead to changes in our brain chemistry, resulting in increased symptoms of depression and anxiety.” That’s… quite scary, actually. Especially considering that, for the vast majority of us, it's not possible to achieve the level of thinness being promoted by the Olandria Carthens and Nara Smiths of the world without dieting, often much more than ‘moderately.’

I don’t think it’s conspiratorial to point out that, if you’re trying to roll back civil rights, including reproductive freedom, equal access to the labour force, equal pay, the ability to leave an abusive or unhappy relationship, adequate healthcare, access to education and voting rights, you’d probably also want to make it harder for marginalized folks, and particularly women, to organize in response, say by ensuring we’re hungry, anxious, depressed and unable to make decisions or solve problems.

@samiahurstmajno Thinness in women is about obedience. And make-up and hairstyles and clothing and and and

♬ the fairy - Ophelia Wilde

And I don’t just mean it’s reasonable to see how that could happen; I mean, it’s literally what has happened before. As mononymous writer Kitty argued in a 2024 essay in Culture Vulture, the pop culture-focused sister publication of Shit You Should Care About, there has long been a relationship between “women’s power and the trend of thinness. The pill was approved for use in 1960, giving women unprecedented bodily autonomy. Jean Nidetch would go on to found Weight Watchers three years later. Roe V. Wade passed in 1973. The decade to follow would be entrapped in a Reagan era conservatism as well as an obsession with women’s athleticism. ‘Perfect womanhood’ began to be associated with ‘hours of pumping iron in the gym’ to draw from a 1986 Chicago Tribune article. The lolly-pop-head body trend of the ‘00s came after an explosion of girl-power media, an increase of women in the workplace and a fleet of legal reforms as well.”

There’s a similar connection between attacking SNAP and social control

Patton makes a similar argument in her newsletter, drawing a throughline from feudalism in Europe, to colonization and enslavement throughout Africa, the Americas and the Caribbean, to Jim Crow-era segregation, to welfare reform in the ‘90s, to modern-day attempts to impose chronic deprivation on vulnerable, and marginalized, members of American society. In medieval Europe between the ninth and 15th centuries, the system of government was feudalism, which was based on land ownership. Royalty granted land to the nobility, who not only controlled the property, but also the labour of the serfs who were bound to it. (This class of peasant literally had to ask for permission from the landowner to move, change their occupation or even get married.)

Serfs weren’t technically considered enslaved because they could not be bought and sold individually, but they certainly weren’t free. In fact, as Patton put it, these peasants lived under a “physiological siege” created through a combination of malnutrition, forced labor, religious terror and the threat of public punishment. Even though some estimates place the number of serfs at about 40% of the English population, they weren’t empowered by their vast numbers. Instead, the threat of fear, scarcity and pain conditioned them to be obedient. And unsurprisingly, every subsequent oppressive force has used a similar model—because, unfortunately, it works.

Starvation is a tool of colonization, weaponized to weaken bodies, fracture bonds, undermine social cohesion, fuel internal aggression, weaken resistance and turn survival into an isolating struggle.

— Yoav Litvin (@nookyelur) July 27, 2025

A thread 🧵 1/

“When people are constantly fighting for food, housing, safety, or rest the capacity for protest shrinks… That’s why every system of oppression starts by attacking the body by triggering hunger, exhaustion, overwork, sleeplessness, fear. If you can dysregulate a nervous system, you don’t need to police the mind because the biology will do it for you,” Patton writes. “Systems of oppression survive by convincing people that hunger, exhaustion and anxiety are personal weaknesses rather than engineered states of control.”

We can also apply this exact same sentiment to the genocides in Gaza and Sudan

Zoom out even further, and you can see this same approach at play in the genocidal campaigns unfolding on social media every day, especially in Gaza and Sudan, where Israel and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) have respectively blocked access to aid. As the UN World Food Programme explained last week, Israel’s attacks on the territory have led to “a complete collapse of Gaza’s food production, job market, economy and infrastructure. More than 80% of Gaza’s farms, bakeries and food storage facilities have been destroyed. Virtually all marketplaces, grocery stores and restaurants are closed or destroyed. Fisheries and farms were once major sources of employment, but those jobs are gone—and with cash critically scarce and food prices sky high, people cannot afford what little food might be available. These catastrophic conditions have left Gazans dependent on humanitarian aid that is often severely limited or restricted entirely.”

Meanwhile, Sudanese people have been experiencing severe malnutrition and famine conditions since 2004 due to an infuriating constellation of factors: the RSF is looting humanitarian aid and destroying harvests, the Sudanese Armed Forces are blocking aid from entering RSF-controlled regions and a shortage in global humanitarian funding means the UN World Food Programme had to reduce the rations it provides in Sudan by 30% back in April. (The org asked for nearly US$800 million from donor states, but received only $102 million of that.) As a result, children are literally starving to death and people are resorting to eating animal feed, even as food rots in the fertile Jebel Marra region, where farmers grow oranges, strawberries, apples and peanuts but can’t get to the country’s biggest markets, in el-Fasher and Tine, to sell.

In both of these cases, hunger is just one part of what people are experiencing right now, in addition to mass executions, horrific sexual violence, displacement and illness. But it is a deliberate strategy that is being used to terrorize and control—with the ultimate goal of destroying a people. As Alex de Waal, executive director of the World Peace Foundation at Tufts University and author of Mass Starvation: the History and Future of Famine, explained in The Guardian earlier this year, starvation doesn’t just have an individual impact; it also undermines community and connection. “Very often that societal element—the trauma, the shame, the loss of dignity, the violation of taboos, the breaking of social bonds—is more significant in the memory of the experience of survivors than the individual biological experience,” he said. “Those who inflict starvation are aware of this, they know that what they’re doing is actually dismantling a society.”

Children are starving in Sudan’s el-Fasher amid 500+ days of deadly attacks and drone strikes.

— AJ+ (@ajplus) October 24, 2025

Local rights groups say around 30 people die each day from hunger, violence or disease. pic.twitter.com/UyS69u4tFi

Obviously each example I mentioned in this newsletter doesn’t describe exactly the same thing—an ill-advised trend involving sunglasses is not comparable to deliberately blocking aid from reaching vulnerable people who are currently undergoing a genocide. But there is a connection. It reminds me of the concept of the imperial boomerang, which describes the phenomenon of colonial powers perfecting their approach to brutality in their colonies, and on their colonized subjects, before returning ‘home’ to the imperial core to subject their citizens to a version of that treatment. Typically, this refers to military might, but I think it also makes sense to apply it to other types of control, from media messaging to bodily autonomy.

And… I don’t have a tidy conclusion, tbh! Other than maybe just to say, once you see the throughline, you can’t unsee it—and hopefully that makes it a little easier to resist, both internally and through our actions.

Thank you for reading this week’s newsletter! Still looking for intersectional pop culture analysis? Here are a few ways to get more Friday:

💫 Upgrade to a paid subscription to support independent, progressive lifestyle media, and to access member-only perks, including And Did You Hear About, a weekly list of Stacy’s best recommendations for what to read, watch, listen to and otherwise enjoy from around the web. (Note: paid subscribers can manage, update and cancel their subscriptions through Stripe.)

💫 Follow Friday on social media. We’re on Instagram, YouTube and (occasionally) TikTok.

💫 If you’d like to make a one-time donation toward the cost of creating Friday Things, you can donate through Ko-Fi.