Those Cardi B ‘BBL Smell’ Rumours Are More Than Just Celebrity Gossip

By Stacy Lee Kong

Image: instagram.com/iamcardib

I don’t know when exactly ‘BBL Smell’ infiltrated my social media feeds, but a) I don’t like this and would prefer it had not become part of the internet’s vernacular, and b) the discourse has really taken off in the past few weeks, which means now we have to talk about it.

For the uninitiated, BBL Smell is exactly what it sounds like: the (alleged) odour associated with Brazilian Butt Lift surgery, a super popular procedure that involves liposuctioning fat from one part of a person’s body—i..e, their abdomen or lower back—and injecting it into their butt, which results in both a snatched waist and a rounder ass. Until recently, the biggest controversy about BBLs, aside from the standard feminist debate on body modification, was how dangerous they are; in the U.S., they have the highest mortality rate of any aesthetic procedure. This is partially due to the surgery itself—according to a 2022 safety advisory from the American Society of Plastic Surgeons, the fat should be injected just below the skin, but it’s extremely easy to go too deep and inject it into the muscle, which can lead to a fat embolism, where particles of fat enter the bloodstream and can travel to the heart or lungs. But it’s also because people are going to sketchy, cheap clinics run by practitioners who don’t have the training or experience to perform this procedure safely.

But over the past few weeks, a new discourse has entered the villa, this one around the rumour that BBLs could develop a terrible odour. This sparked many a salacious headline (The New York Post: “Disgusting ‘BBL smell’ side effect might make people reconsider getting popular surgery”; Vice: “‘BBL Smell’ Is Real—and Just as Gross as It Sounds”; The Sun: “My botched BBL left me stinking of rotting flesh & my boyfriend left me over it”). And there was even a celeb connection—a few days ago, a rumour began trending on social media that Cardi B’s new boyfriend, New England Patriots wide receiver Stefon Diggs, had dumped her over the smell of her BBL. Both she and Diggs denied they’d even broken up, much less that the cause was the way her body smelled, but that news story, in combination with the spiking interest in the phrase BBL Smell, finally caught my attention.

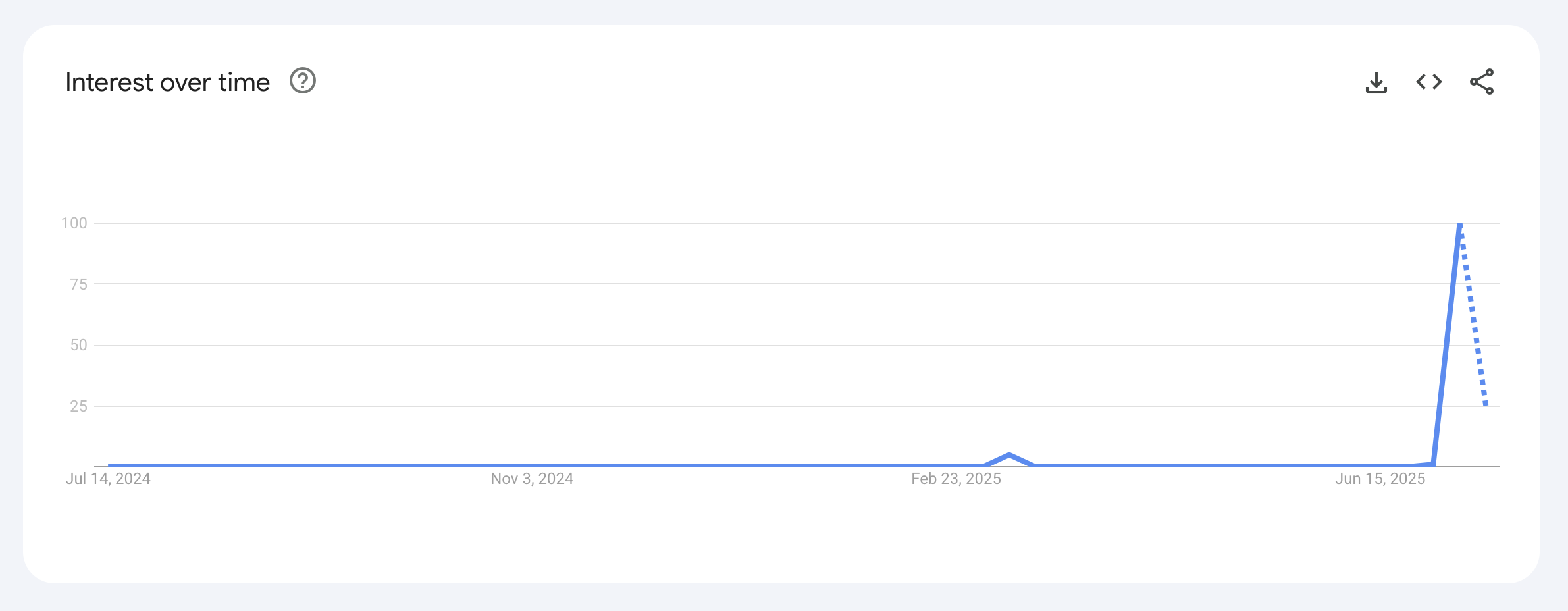

And when I say ‘spiking interest,’ I mean it. Per Google Trends, the phrase had garnered next to no search traffic over the past 12 months, until a sharp rise at the end of June. Similarly, while this conversation has regularly come up in both plastic surgery and pop culture forums, as well as in coverage from a few outlets (almost always because of a viral social media post), the bulk of the news stories I’ve seen were published in the last two weeks. I’m not sure what scandalous TikTok or podcast clip sparked this wave of attention, but honestly, it doesn’t really matter, because the more interesting thing to think about is definitely the connection between femininity, smell and shame.

First of all, I’m not convinced ‘BBL Smell’ is even real

Before we get there, though, a tiny bit of media criticism. Almost all of the coverage I’ve seen over the past two weeks reports on this purported odour in a way that I find quite confusing, not to mention factually iffy. It is possible for someone who has gotten a BBL to smell; the thing is, that’s not specific to the procedure.

In its most recent story about this topic, the Daily Mail (I know, I know) quotes Chicago plastic surgeon Dr. Eric Anderson, who says “the BBL smell is real,” before going on to explain that “it can be caused by a number of things, including tissue death and unhygienic practices.

“One complication of BBLs is ‘fat necrosis,’ which causes fatty tissue in the buttocks to die following surgery, ‘an indicator that a patient was overfilled with fat during the procedure.

“When there is more fat in an area than the blood supply allows, the fat will die through a smelly process called fat necrosis, which can lead to infections that need antibiotics, hospitalizations, and even sepsis.’”

@doctoryoun Is the BBL Smell REAL? Do you smell bad after getting a BBL? Here’s the answer! #bblsmell #bbl #plasticsurgeon ♬ original sound - Doctor Youn

The story says poor hygiene could also explain an odour, as could infection or the fact that “the body is draining fluids, and the patient is wearing tight compression garments that can trap sweat, moisture, and bacteria against the skin.” That last bit is per New York-based plastic surgeon Dr. Douglas Steinbrech. Please note, all of these explanations are actually just due to having a body, and according to the experts’ own quotes, not one of them is specific to BBLs—not even fat necrosis, which btw, other plastic surgeons quoted in far more credible outlets say is usually odourless.

So, what these doctors are actually communicating, once you strip out the bombastic quotes, is that the only time a BBL should emit an odour is if something is wrong—either you’re not able to clean yourself properly, or you have an infection or complication. But the framing of each article says the opposite: that there is an odour specific to this procedure. Of course, if you read several of these articles, you see that many, if not all, of the ones that proclaim BBL Smell is real actually just picked up the Daily Mail’s reporting and are recycling Dr. Anderson’s quotes. However, the bigger problem is that the quotes simply don’t back up the thesis of the article, and maybe I’m being extra here, but I think that’s a problem. Journalists have a responsibility to be accurate in all parts of the story, including what it implies or alludes to. Philosophically, this is an important element of journalistic integrity. But also, this kind of reporting comes with a real risk of perpetuating stigma, which doesn’t actually make anyone healthier. (Again—highest mortality rate of any aesthetic procedure.)

I will absolutely take this opportunity to talk about the politics of smell, though

Also, It’s not an accident that BBL Smell is trending now. What I think we’re seeing is a cultural desire to punish women for not adhering to today’s trending beauty standards. I referenced this last year in my newsletter about Lindsay Lohan’s new face, but it’s even more relevant here: In the West, we are moving to a new must-have body type and overall aesthetic, and it’s one that emphasizes or mimics whiteness, in everything from body type to makeup styles. There’s data to back this up; in November 2024, The Hollywood Reporter reported on the “de-Kardashian-ification of America,” citing plastic surgeons from New York and L.A. who were seeing their customer base demand more subtle, natural-looking augmentation, instead of Kardashian-style curves. (This is an aesthetic evolution that we’ve even been seeing among the famous family themselves, for the record.) I’m not saying this is logical, or even conscious, but it does feel like there’s a sort of collective shaming of women who invested their time and money, and risked their health, to achieve a body type that is falling out of (mainstream, white) fashion.

And smell is a powerful way to do that. As my current favourite academic, Ally Louks, explained in an article for The Conversation, “it is well documented that smell has been used as a justification for expressions of racism, classism and sexism. Since the 1980s, researchers have been assessing the moral implications of perceptions and stereotypes related to smell… I suggest that smell very often invokes identity in a way that is meant to convey an individual’s worth and status. In Parasite, for instance, a working-class man overhears his employer say that his ‘smell crosses the line,’ which the director describes as a moment when ‘the basic respect you have for another human being is being shattered.’”

not that i think most “critics” here are genuinely wondering what dr louks means by “the politics of smell”, but if you are, i suggest watching this clip from Parasite (2019) where the CEO father talks about his new personal chauffeur’s smell https://t.co/5JPFSrUckz pic.twitter.com/37J8U37A2O

— juan² #BLM #CeasefireNow (@juanxjuanisjuan) December 2, 2024

Similarly, in this discourse, the internet at large is communicating its lack of respect for women who get BBLs by enthusiastically embracing the idea that they smell; the implication is that they are worthy of disgust, and the undeniable signal of their digustingness is a lingering odour that they can’t contain or solve. (According to Louks, there is an explicit link between smell and disgust, and when we “when we're talking about smell and using it to create prejudices, i.e. to make prejudicial statements, what we're doing is we're mobilizing disgust.”)

This isn’t just gendered; there’s also a racial element. As we all know, the ‘Kardashian physique’ is actually an amalgamation of physical characteristics that have traditionally been markers of beauty for Black women: big breasts, a tiny waist, curvy hips and butt, dark skin, bee-stung lips. Not that this standard is actually accessible for all Black women, of course. As Unbothered noted in 2023, “between 2015 to 2019, the number of butt augmentation surgeries increased by 90.3% and the number of Black patients increased by 56% [and] videos of Black women wearing a faja (post-operative shapewear) are becoming more prevalent on social media.” To be fair, these surgeries have always been controversial, and critique doesn’t just happen between communities, but also within them—Unbothered notes that “on Black Twitter, BBL bodies are often treated like a caricature and subject to widespread ridicule.” But the point stands that BBLs are racialized in the public imagination, and that critique has always had elements of anti-Blackness. Now, though, that critique is intersecting with ideas around hygiene and disgust. I mean, in general, racialized people are both more likely to be perceived as dirty by white society and (unsurprisingly) more invested in hygiene as a social norm. As I noted in a 2021 newsletter on that year’s celebrity hygiene discourse, “racialized people are constantly surrounded by messages about our fundamental dirtiness—see: every advertising campaign for a skin lightening product, plus some that are supposedly just about getting clean, like a 2017 body wash ad that showed a ‘dirty’ Black woman turning into a ‘clean’ white one. And it’s not just race—fat and disabled people receive very similar messages.”

Hygiene discourse comes for us all

All of this directly plays into what we’re seeing with Cardi B. But while I’m empathetic to Cardi, who was clearly, and understandably, angry at the implication that she smelled bad, I do think it’s interesting to note that she has spread similar ideas herself.

A gorgeous and talented woman, undoubtedly, and I am in no position to question this tweet. The desire to present oneself as odourless, though, could be seen as a preventative measure against disgust, which speaks to the widespread association between women and malodour. https://t.co/AqeQfxT2kr

— Dr Ally Louks (@DrAllyLouks) December 18, 2024

In response to the rumours, she addressed her followers via Twitter Spaces, saying, “First of all, I don’t know who made that up… But bitch, that’s you… That’s on you, bitch. That could never be me. Bitch, I was a fucking stripper, you had to smell good all the time. I was raised by women, like please.” This alone contributes to wider ideas about propriety (“I was raised by women”) and uses perceived smelliness as a weapon against other women "(“bitch, that’s you”). But also, in December, she responded to an internet troll who questioned her sense of self-worth by naming her positive traits, which included never smelling bad, even during her period.

I’m not saying I’m immune to the societal pressure or cultural desire to smell good. I am not! But… the way we talk about women and smell is directly tied to power and control; women’s bodies, and our normal bodily functions, are considered things to be sanitized, policed, solved. If we don’t adhere to the social norms that dictate what our bodies should be like—ideally unobtrusive and inoffensive in size, shape, smell, etc.—then we are ‘bad’ at womanhood, which is especially true for women who already don’t fit into white, Western frameworks of femininity.

And sure, it’s not all misogyny. There is also some capitalism at play here. But a lot of it is about signalling our moral purity through compliance. So, while it’s fucked, it’s not surprising that Cardi could both weaponize this type of misogyny against other women and have it weaponized against her. Because unfortunately, compliance is actually no protection at all. Misogyny will get us, every time.

Thank you for reading this week’s newsletter! Still looking for intersectional pop culture analysis? Here are a few ways to get more Friday:

💫 Upgrade to a paid subscription to support independent, progressive lifestyle media, and to access member-only perks, including And Did You Hear About, a weekly list of Stacy’s best recommendations for what to read, watch, listen to and otherwise enjoy from around the web. (Note: paid subscribers can manage, update and cancel their subscriptions through Stripe.)

💫 Follow Friday on social media. We’re on Instagram, YouTube and (occasionally) TikTok.

💫 If you’d like to make a one-time donation toward the cost of creating Friday Things, you can donate through Ko-Fi.