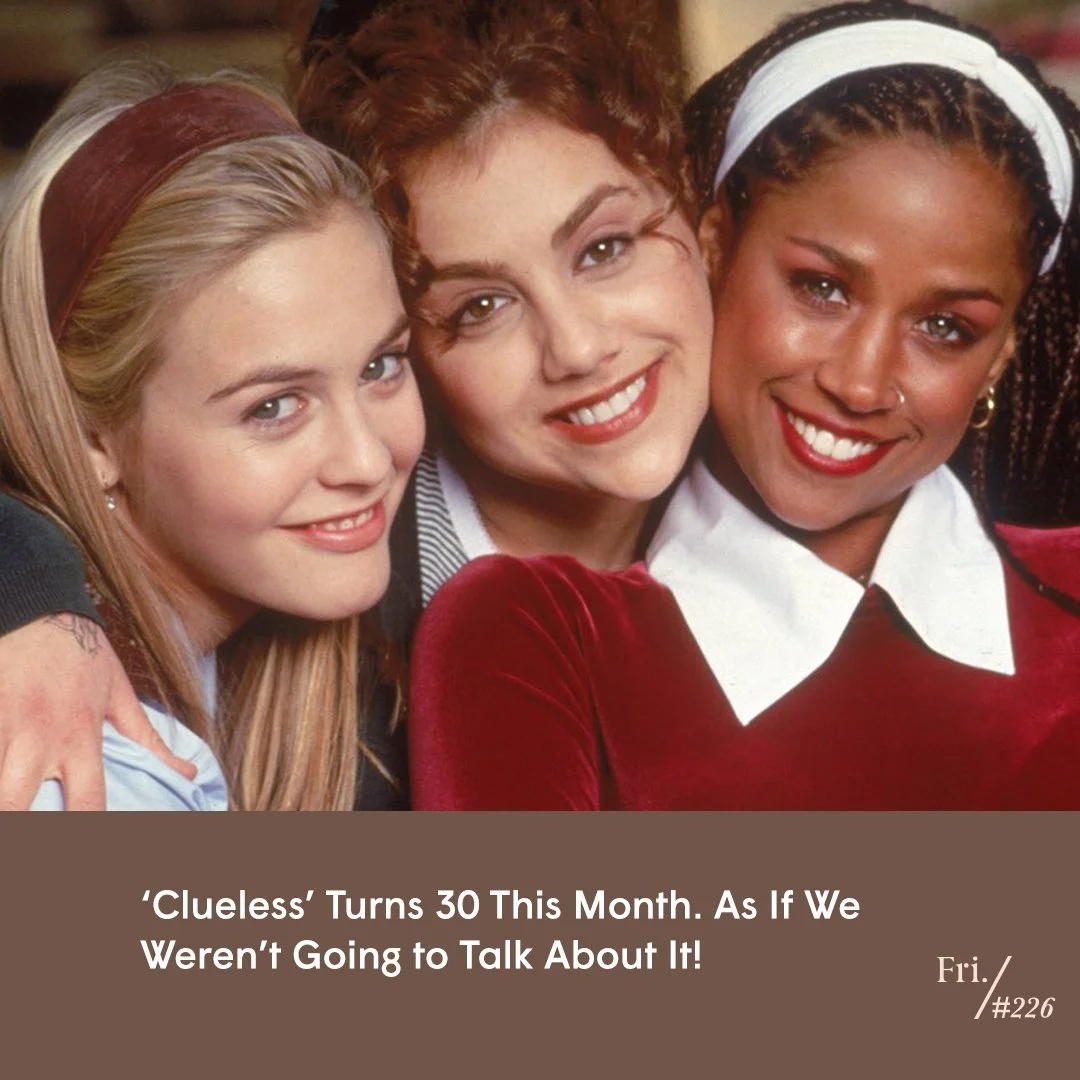

Why We're All Still So Obsessed With 'Clueless'

By sTACY LEE KONG

Image: instagram.com/clueless

I don’t know if anyone could have imagined that valley girl Cher Horowitz, the protagonist of a 1995 teen comedy based on the Jane Austen novel Emma, would remain not just a recognizable pop culture figure, but in fact an iconic one, three decades after she whatevered her way onto movie screens and into our hearts. But that’s what has happened—references to Clueless still show up on the runway, in advertising, and in other pop culture. It always feels a little weird if I don’t see at least one couples costume (Cher and Josh, sure, but preferably Dionne and Murray) every Halloween. The movie even provides inspiration for actual tech advances! (Why yes, I have periodically wondered why I do not yet have Clueless closet technology, why do you ask?)

But I’d argue that the appeal of Clueless isn’t just because it’s fun, though it really, really is. There’s also a lot that’s worth thinking about: how the movie approaches race and class, what it tells us about love and friendship, and of course how femininity is perceived, and sometimes weaponized. And there’s no better person to discuss all of this with than Veronica Litt, author of Ugh! As If!: Clueless, a new ECW Pop Classics book about the movie. Read on for our chat about the movie’s staying power, the thorny questions it raises and how we interact with it as a fans.

Why Clueless?

I’ve been a fan of the Pop Classic series for a long time. I've read all the books in the series, [but] the one that had the biggest impact on me was the one on The Bachelor by Suzannah Showler. It's genuinely a brilliant book, and it really opened my eyes to seeing pop culture, and especially ‘girly’ pop culture, differently. So, I knew I wanted to pitch the series, but it was a matter of what I wanted the project to be on. At the time, I was really interested in things like romance in popular culture, male love interests in popular media, the idea of ditzy characters and innocent white women, colorblindness and race. And, I have a PhD and was really into Jane Austen for so much of my life. So I thought, ‘Okay, if I want to talk about all these things—friendship, romance, love, pop culture, Jane Austen—they all really coalesce in only one thing, and that’s Clueless.’

Author Veronica Litt. (Image: Mitch Johnston)

Related to that question, why now? By which I really mean, why do you think the movie is still popular (and relevant!) enough to justify this type of analysis, 30 years after it came out?

I have a couple theories. The first one is, it's working with source material that we tend to think of as timeless. There's still that appetite for Jane Austen novels, which may be because her books are about the bread and butter of emotional daily life. They’re about people bopping through the world, trying to find love, trying to navigate family and friendship, and that never goes out of style.

I also think there's a very good-hearted message to the movie. The world is bad. A lot of the time, it's hard to [face] how horrific it can be. So, at least for me as a viewer, I need comfort watches and moments of relief and reprieve, and I think Clueless is a good example of that. Edutainment is brutal. When I watch a movie that wants to instruct me, I want to eat my own head; it just feels so try hard and so obnoxious. But this movie is snarky enough, and has enough jadedness and rough edges, so I know we are not in this magical world yet—but there’s this really beautiful beating heart of optimism underneath that. I think that is a really good way to bring people in who, like me, have been trained to think, ‘The world can't change. Be realistic’ but still want to think it can.

Those are my rosy ideas for why it's still relevant. At the same time, it's a complicated movie, right? And some of the things we return to again and again in it are not particularly comforting. In the chapter I wrote on class, I talk about how very eerie it is that Amy Heckerling had to change so little about a novel from 1815 for it to work in 1995. So, some of those evergreen themes are ones I don't want to be evergreen—like the really downplayed Black best friend, or the working class girl whose main role is to educate this rich white kid. We go back to this movie, and we don't often really think about these things directly, but they're kind of pernicious. So, on the one hand, lots of reasons to love it, and on the other hand, maybe also have a thought or two about it.

That’s my ideal way of engaging with pop culture, honestly. I interviewed Andrea Warner last year for her Pop Classics book about Dirty Dancing, and we touched on something that I want to ask you, too: what do you think is behind our current impulse to look critically at things that we loved 10, 20, 30 years ago? Is it just nostalgia, or is it more complicated than that?

I think there is definitely a nostalgia angle. And maybe a sociologist would say, ‘Well, duh, all these millennial women grew up with this art, and by the time they're ready to write a book, this is what most compels them.’ But I think there’s something else going on, too, which is, it's really, really hard to see the water you swim in. There are all these things this movie internalizes and naturalizes and doesn't think twice about, and now, because there's more of a critical distance between us and it, we’re able to see it in a way that maybe we couldn’t see it before.

It's obvious that you're writing this book from the perspective of someone who loves this movie and sees a lot of value in it, but I do appreciate the way you look at how identity and oppression are portrayed in Clueless. What do you think the movie loses by not meaningfully addressing race, especially since it treats other identities—like queerness—with more sensitivity?

I have problems with the queerness stuff too, but it does have a better reputation [there]. The character of Christian is so, so idiosyncratic; he’s not a stereotype. But on the race angle, I think it loses a whole lot. I think the most immediate thing it loses is that it’s meant to be a story about friendship, but I just don't see that friendship between Dionne and Cher. It lacks substance because you just have no entryway into Dionne’s inner life. I think she's an amazing character, and Stacey Dash’s comic timing is amazing. Her performance is remarkable—she's so classy and sassy and funny and glamorous. A lot of people defend Clueless by saying it’s a movie about an interracial best friendship. But I find that that’s not quite what it is, because you only get a very superficial layer of friendship between those characters. So, you lose out on your ability to see that one character in all her depth. You also maybe see—and this is something I write about in the ditz chapter—that there are all these little tells that this main character is not as appealing as you'd like her to be. She has no curiosity about her friend, and that is not a good trait, right? There's innocence, and then there's willful ignorance, and maybe the race sections of the movie get us to this idea that, ‘Oh yeah, this ditz is hardening into someone who cannot, or will not, see this.’

I love that you make that point, because I don't think I had really thought about what it means to be in an interracial friendship and refuse to see race in the context of Clueless, and what the implications of that might be for the story. Which is interesting because that friendship is such an integral part of the movie.

Sometimes I'll hear from people who think that chapter feels a little unfair, because if the movie integrated those concerns, it no longer would be Clueless.

But not integrating it makes it actually quite realistic, I think. When you are in an interracial friendship—or any kind of relationship, really—there can be times when you aren't being fully ‘seen.’ There are big parts of your experience that aren't being fully acknowledged by the more privileged person in the relationship. So it just takes a little mindset shift to see, as you're saying, a little hint of, ‘Well, this friendship is not really what we want it to be’ or ‘This protagonist is not quite what we want her to be.’ And that's quite reflective of real life.

Oh, that's really interesting—this idea that the part of this movie that is realistic is the ugly part, that you have to cordon off this part of your life because that white friend doesn't really want to hear about it, or maybe won't respond well when it's brought up. Part of this was inspired by my friendship with my buddy Joan. This was back during the George Floyd summer, and I remember we had this group chat with all our friends from high school and university, and it just wasn't being brought up at all. No one was bringing it up, and I felt like it was massive news. It was everywhere. So, eventually I brought it up, and my friend messaged me and was like, ‘I'm glad someone said something, because I felt like I was going nuts.’ And I wondered, how many times this had happened. So researching that chapter made me see my life and experiences differently too, right? I think good art can implicate you in a way that's constructive.

Going back to the idea of people loving and wanting to defend this movie, I have written and talked about lots of things that can spark defensiveness, sometimes in surprising ways. People are very defensive of Friends. People are very defensive of Gilmore Girls. Clearly, people are also defensive of Clueless. Another defence that I get a lot is that these things were created in a different time, so it’s not fair to judge them by today’s standards. What do you make of that?

I mean, it's such a knee-jerk defence, right? But it’s also just not a convincing argument at all, because, yeah, it was a different time, but it's not like people of colour hadn't been invented. You can go all the way back to a Victorian novel with really regressive gender politics, and people can say well, they hadn't invented feminism yet. But actually, proto-feminism was on the rise well before that. To go back to what we were saying about being able to see the good and bad things about the art that you really love, it’s good to hold those two things in different hands. It wouldn't be realistic or honest to see something as entirely good or bad. So, why do you need to protect this thing? Why can't it withstand a little bit of criticism?

Those are good questions. I do think that so much of our politic, especially in contemporary feminism, is tied up in what we consume, so a critique of what we buy is also a critique of ourselves. Okay, last question: Early on in the book, you have this line that I really like: “Clueless argues that idealism is more useful than cynicism, that hope is more powerful than despair and that community is more valuable than isolation.” How do we feel about that being a powerful message in the 90s, but still a powerful message today?

When you look back at what movies about high schoolers were made in the ‘90s, it was very dark, very doom and gloom—and also very much about boys. So Amy Heckerling comes in and says, ‘I'm going to make a really bright, happy, hopeful movie about this girl,’ and it does what none of these movies can do. Cher has the innocence, or idiocy depending on how you see it, to look at a flawed world and not just be like, ‘Okay, yeah, it's terrible.’ Instead, she's like, ‘I want to help.’ There's this really sweet, simple line at the end of the movie where it finally clicks and she's like, ‘Oh, right, these people at Pismo Beach are suffering,’ and she just wants to help them. It's such a sweet reaction, and it [gets at] something that definitely stays true today. With social media and the 24-hour news cycle, it feels like you're surrounded by the worst things in the world. I think about Gaza all the time. How could you not? But, what do you do? So it can be really easy for me, at least, to fall into this paralysis of passivity, where it's like, I call and I donate, and yet I don't see things changing. It can make you wonder, why do I even try?

And when that happens, I think you need to turn to art that is regenerative, and insists that yes, trying makes a difference. Trying is good. Trying is worthy. And actually, the work of trying can have this degree of fulfillment. Because that's the other thing—one of the things that's nice about the movie Clueless is that it depicts social progress as inherently pleasant and happy. The work of making a world better is happy, nice work. So, in this world, where that work just feels so terrible, maybe we need to be reminded that it is worth it, and that it can be pleasurable—and then you go back into the muck. I think that's why I find the movie resonant, even today, even with all its limitations.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

Ugh! As If!: Clueless by Veronica Litt is out now. And, for Toronto readers, Veronica will be hosting a screening of Clueless and after-movie chat at the Paradise Theatre on July 24 at 7pm.

Thank you for reading this week’s newsletter! Still looking for intersectional pop culture analysis? Here are a few ways to get more Friday:

💫 Upgrade to a paid subscription to support independent, progressive lifestyle media, and to access member-only perks, including And Did You Hear About, a weekly list of Stacy’s best recommendations for what to read, watch, listen to and otherwise enjoy from around the web. (Note: paid subscribers can manage, update and cancel their subscriptions through Stripe.)

💫 Follow Friday on social media. We’re on Instagram, YouTube and (occasionally) TikTok.

💫 If you’d like to make a one-time donation toward the cost of creating Friday Things, you can donate through Ko-Fi.