It Really Is That Deep, Fast & Furious Edition

By Stacy Lee Kong

Image: Universal Pictures

It’s hard to believe, but we’ve been watching Vin Diesel lead a team of charming and good-looking car thieves for almost a quarter of a century—The Fast and the Furious, the first film in what would become Universal Pictures’ most lucrative franchise, debuted in 2001 and turns 25 next June. In that time, Diesel and his co-stars became increasingly marketable, not to mention powerful; the movies got increasingly over-the-top; and slowly but surely, Fast established itself as a pop culture tent pole and an industry bellwether. At least, that’s the argument Barry Hertz is making in his new book, Welcome to the Family: The Explosive Story Behind Fast & Furious, the Blockbusters that Supercharged the World. He’s the deputy arts editor and film editor for the Globe and Mail, so Hertz definitely knows what he’s talking about. That’s why, in this week’s newsletter, we’re chatting about the lasting appeal of the movies, the impact they’ve had on the industry and the fascinating politics of the Fast & Furious franchise.

First, a very basic question: why write a book about The Fast and the Furious franchise?

I’ve always been a huge admirer of the series. For people who know my day job, they’re like, ‘Huh?’ But I’ve always considered myself a big-tent movie goer; I like art house, I like indie, I like foreign language, I like experimental, I like big, juicy, meaty, dumb blockbusters—so long as they’re done well. I’ve followed the series since I was a teenager, and I’ve just always really admired how crazy they became, from this tiny, relatively grounded street racing movie to a globe-trotting spectacle that has actually crossed the exosphere of planet Earth. In tandem with that, it’s always been such a fascinating franchise to follow off-screen, because there have been so many dramas, personalities, huge egos and Hollywood politics at stake. The franchise will be 25 years old next year and when I started to think about it deeply, I was like, ‘You know what? You can measure the past 25 years of Hollywood through the past 25 years of Fast & Furious.’

Image: Jenna Marie Wakani

In the introduction to the book, you make that same point, saying, “the past twenty-five years of Fast represent the innovations and tensions of the past twenty-five years of Hollywood—maybe even the past quarter century of globalized pop culture itself.” That’s quite a big statement to make about a series that doesn’t have a critical or popular reputation as ‘important.’ Like, I have very fond memories of the series because my dad and I watched most of them together, so there’s definitely an emotional part to that, but I still mostly love it in a tongue-in-cheek way.

I love it sincerely and ironically. In terms of those tensions, I think there’s a lot of different elements you can kind of pick out. Perhaps the one that’s most in your face is this has become the most diverse franchise that Hollywood has ever made, by far. And it did so before diversity was some kind of mandate in the industry; this was happening very organically, because it was seeking to accurately represent the subcultures that it was chronicling. This was starting off with SoCal racing culture, which was very much a Latino thing, it was very much part of the Asian community, it was very much integrated into the Black community. It wasn’t necessarily siloed; it was, well, you can be part of this scene so long as you can drive and you have a cool car. The colour your skin doesn’t matter so much as the make of your engine. And of course, Vin Diesel is this very ethnically ambiguous guy who can represent a lot of different cultures. You can see yourself through Dom Toretto, regardless of what your background is, or what his specific background is. And they have been very… let’s say generous and elastic with what that background is as the series has evolved. We discover in Fast Eight that he’s got family in Cuba. There’s a Toretto cousin there for some reason. And in number four, he’s got background in the Dominican.

The decision to prioritize belonging feels like it relates to the way the series emphasizes family. Like, the idea of family is a narrative throughline, but it’s also important behind the scenes, because Vin Diesel’s marketing talking points heavily lean on the idea of chosen family.

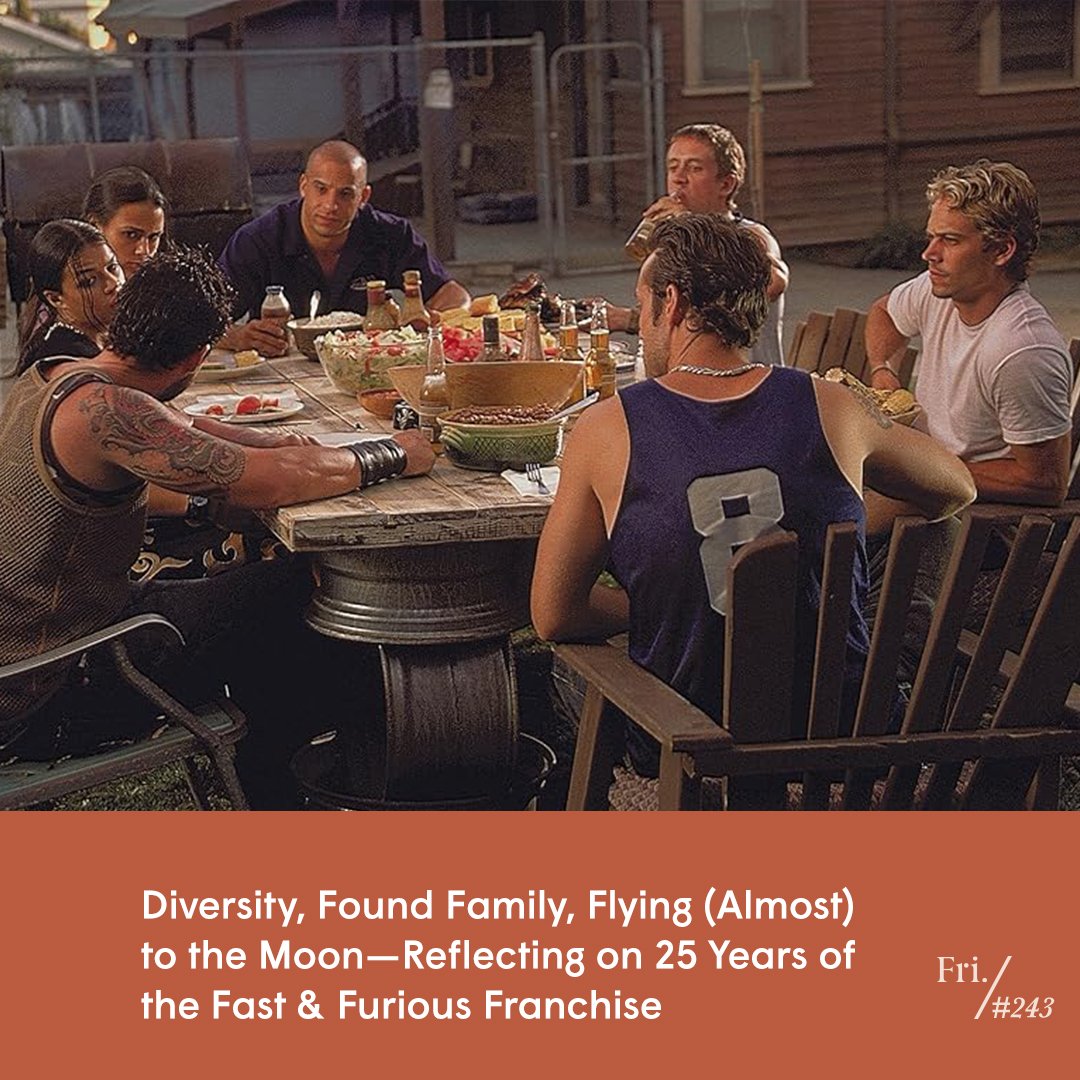

The family element was baked in to the very beginning, with the Paul Walker character joining the Vin Diesel character as brothers from different mothers. And all of Dom’s crew hung out at that big house in Echo Park, which was a working class neighborhood. They’re all barbecuing in the back, and nobody there was related by blood and really, they were all kind of orphans in their own way, but they found each other through this common cause. So you build on that sense of affection and loyalty, and it becomes something that really attaches itself to the audience. Because it’s weird, these movies are not a typical Blockbuster where it ends with a couple embracing after defeating unstoppable evil. Or, even one person standing atop a mountain of defeated henchmen. It ends with people hugging together over barbecue chicken and a beer, brother hugging brother. There’s a lot of platonic love.

Yes! When you think about the tension of the first movie in particular, which I think does it the best of all of the movies, you’re worried that Paul Walker dating Vin Diesel’s sister ruins their relationship. The central relationship—the thing you’re most invested in—is those two bros.

Exactly! Which is quite sweet, actually. Normally it would be the man and the woman in the friendship and it’s like, Okay, are we going ruin the friendship by becoming romantic partners? But this one, you’re like, Whoa, whoa. Let’s make sure the bros are okay here.

So, I’m obviously interested in this because I’m a journalist, but I didn’t realize the first movie was based on a Vibe article! I was so fascinated by the paragraph where you were quoting Kenneth Li, the writer, about how different it would be if he was writing that piece now, because he wouldn’t own the copyright. His tiny involvement would have been even less.

I found that line to be such a ‘there but for the grace of God’ kind of moment. I think if you did a poll, 90% of people who watch these movies would have no idea it had any kind of underlying intellectual property at all. [As it is,] he gets this tiny little credit in the very end credits of the first movie, and then disappears. But without that grounding and the authenticity that Kenneth Li was initially seeking for that Vibe piece, you wouldn’t have the base of the first film, which was very much seeking to represent an authentic culture and an authentic scene that was happening in Queens, back in the late ‘90s. The journalism world was very different back then, and the freelancer had rights to his own material, so he was able to option it to Universal.

It feels like there are lots of examples like that, where the movie, or some part of the lore of the movie, is illuminating the way media and entertainment businesses have evolved. Were there other things that stood out for you?

Oh yeah, tons. Initially, I was going to take a much more industry-heavy approach to it, because that’s a little bit more of my comfort zone, in a way. I quickly realized that this was not a film industry book and I had to expand it a little. But, one of the big things was the DVD market. So the first film was a very big success theatrically; it made its production budget back and then some on its opening weekend, which nobody involved with the movie really expected. But, it really only became this cash cow and a franchiseable' property because of the home entertainment market.

I think the first movie sold the most DVDs in Universal’s history up to that point. It was an early time in the DVD market, but studios treated it as a gold mine because it was found money. It didn’t cost a heck of a lot to produce or market, and they didn’t have to split the revenues as disproportionately as they did with movie theatres, because 50% of the box office revenue goes to the theatre owner. Some of the revenue from DVD sales obviously goes to the retailer, but a much larger chunk of change goes to the studio. So many movies found their success this way, and became franchiseable series because they were earning tons of money on DVDs. When it was VHS, there was a an element of retail, but it was nothing like the DVD market. Back then, if you didn’t see a movie in theatres and you didn’t want to wait two years before it came on to television, DVD was your entry point. So, people were buying up DVDs like crazy. Now, that’s completely disappeared. It’s a niche market, if anything, and studios have had to watch their profits drop precipitously, because streaming and digital electronic sales of movies are not commensurate with what they would have made on DVDs. Fast very much owes its life to the DVD timing, as do a lot of franchises, like Bring It On and American Pie. Those would not have survived as long, were it not for that DVD thing. So that was something that was very interesting to learn about.

You spoke with about 200 people for this book, but your list of potential interviews was much longer—which makes sense because so many people have been involved with this series over the years. How did you frame the book in your head so that you knew who you needed to talk to?

The benefit of this being a long saga is that I always knew I wanted to organize it chronologically, one movie per chapter, going forward in time—with some diversions, of course. But I went in with framing of, well, I know what I want to say about these movies. I know I like these movies, and I love talking about them, but I only know so much. [So] here’s how I think the series reflects the evolution of Hollywood, but it was really more of me trying to understand how they were made. For most of the people I approached, it was like, what was your involvement in this? What was your timeline? What was your most memorable experiences? How did this come together? It was really just trying to get everybody’s memories and perspectives and experiences together, collate that, and then filter it through, each film. And then, you know, try to craft a narrative out of that.

There are mentions of the sexual assault allegations against Vin Diesel at the beginning and end of the book. [Ed note: A California judge dismissed that lawsuit this week.] How did you approach handling that part of the story?

I just tried to be as well-rounded as possible. It book-ends the book, because it’s not a footnote. There’s lots of footnotes in the book, but you can’t talk about one thing without acknowledging the cloud that hangs over the rest of it. It was challenging because I love these movies, and I love the work that he does in these movies, but you can’t just ignore context. So that was tricky. And because of that, it was not surprising that he didn’t want to speak to me, and that a lot of the cast did not want to speak. I did get word from one of the main players, who was basically like, “You know, your approach is really interesting. I’d love to talk and tell you my experience on the films, but unless Vin agrees to do it, I’m not going to do it.” That speaks, I think, to the degree of loyalty that he has engendered among the filmmakers and the participants in the movies. But it was tough.

We talked a little bit at the beginning of our conversation about diversity being the root of this franchise, and these ideas of family, chosen family and love—but the other side of that is who’s in the family, and who’s not. So, in 2017, Michelle Rodriguez threatened to quit the franchise in an Instagram post. Specifically, she said she might leave if she and other female characters did not get better treatment on-screen. Obviously she hasn’t done that, probably for economic reasons and, as you just said, out of loyalty. But that post still speaks to a tension between what the movies seem like they stand for and what they actually do. So I’m really curious what you think about the politics of this franchise.

I started playing this speculative game with myself a little while ago: if the Torettos were in the real world, who would they vote for? Because I mean, [the movies] don’t really stand for anything, except for that very apolitical notion of family—and you will find that sentiment of family is everything, protect family at all costs on any side of the polarized debates. That said, [the first movie] is very much a pro-immigrant story about pulling yourself up by your own bootstraps and going against the authoritarianism of the world. There’s a rebellious streak there, against authority and positions of authority. But as the movies go on, that does get a watered down, because the crew gets co-opted by the U.S. government, through either Dwayne Johnson’s character and his agency, or through the Kurt Russell character and his Black Ops thing, which has no allegiance to anywhere in the world.

The movies very clearly do not want to define themselves as political in any way, just like a lot of big, huge blockbusters wouldn’t, for fear of alienating a portion of their audience. But politics are there, and the gender dynamics are very prevalent. The filmmakers did slightly hear Michelle Rodriguez’s complaints, and they did bring in Suzan-Lori Parks, who’s the first Black playwright to win a Pulitzer for drama, to work on some additional dialogue and beef up the female characters and the conversations they were having in those movies. But that really only started with Fast X.

Earlier, you said when you started working on this book, you knew what you wanted to say about the series. What as that central message you were trying to communicate?

If I had to boil down to one, is that these have been the most successful and accidentally prescient movies Hollywood has made, that we have all collectively taken for granted. We all kind of think, ‘Oh, The Fast and the Furious is a pretty dumb movie, though I guess it’s pretty successful.’ A lot of audiences and critics underestimate the massive financial domino effect these movies have had, not just for their producers and their studio, but for the rest of the industry. And even on the way movies are made—in discussions of cultural diversity, in opening up an attitude on American cinema to the rest of the world. We didn’t really touch on how these movies made really huge inroads in China and South America, and really became a global ambassador of a franchise. Even in innovation and visual effects, just with the Paul Walker stuff. That was such a huge part of its story and evolution and, and we’re still reckoning with that today. You know, what are the ethics, what’s an actor’s autonomy once they’ve passed? We’ve seen it be explored in a lot of different ways recently, and I feel it’s only going to get more of a tricky subject. This certainly was one of the first films that really, fully, digitally resurrected a character, and it has a lot of implications for the rest of entertainment. So I think I just felt the series was never really given its proper due or respects in the discourse, and that was what I was hoping to achieve.

Welcome to the Family: The Explosive Story Behind Fast & Furious, the Blockbusters that Supercharged the World comes out on November 25, 2025.

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Thank you for reading this week’s newsletter! Still looking for intersectional pop culture analysis? Here are a few ways to get more Friday:

💫 Upgrade to a paid subscription to support independent, progressive lifestyle media, and to access member-only perks, including And Did You Hear About, a weekly list of Stacy’s best recommendations for what to read, watch, listen to and otherwise enjoy from around the web. (Note: paid subscribers can manage, update and cancel their subscriptions through Stripe.)

💫 Follow Friday on social media. We’re on Instagram, YouTube and (occasionally) TikTok.

💫 If you’d like to make a one-time donation toward the cost of creating Friday Things, you can donate through Ko-Fi.