How Do We Talk About Ariana Grande's Weight Loss?

By Stacy Lee Kong

Image: Shutterstock

Content warning: This newsletter contains references to, and descriptions of, disordered eating.

Two years ago, Ariana Grande posted a TikTok asking people to stop talking about her body. She was responding to commentary about her appearance in then new promotional photos for her beauty line, R.E.M. Beauty, which sparked a deluge of comments about how much weight she’d lost since 2020. In response, Grande said, “I think we should be gentler and less comfortable commenting on people’s bodies, no matter what… [That was the] unhealthiest version of my body. I was on a lot of antidepressants and drinking on them and eating poorly and at the lowest point of my life when I looked the way you consider my healthy. But that in fact wasn't my healthy.”

Aside from the implication that being on antidepressants is unhealthy, it was a fair ask. She opened the video by talking about how weird it was “to be a person with a body and to be seen and paid such close attention to,” something we have seen female celebrities navigate in increasingly disturbing situations for decades now and, I’m willing to bet, have experienced ourselves, albeit on a much smaller scale. We know how awful it is to be surveilled and judged like this—I’ve written so many newsletters about the way media and the general public police female celebrities’ bodies, to dangerous, if not disastrous, effect. This is why one of the cardinal rules of modern feminism is don’t talk about people’s bodies. Don’t comment on how much weight they’ve lost (or gained), don’t assume they’d prefer to be smaller and definitely don’t compliment weight loss, which communicates that being thin is naturally better than being fat. The goal is to dismantle fatphobia, and to slowly but surely push us toward a world where the size and shape of our bodies don’t function as indicators of our value.

But.

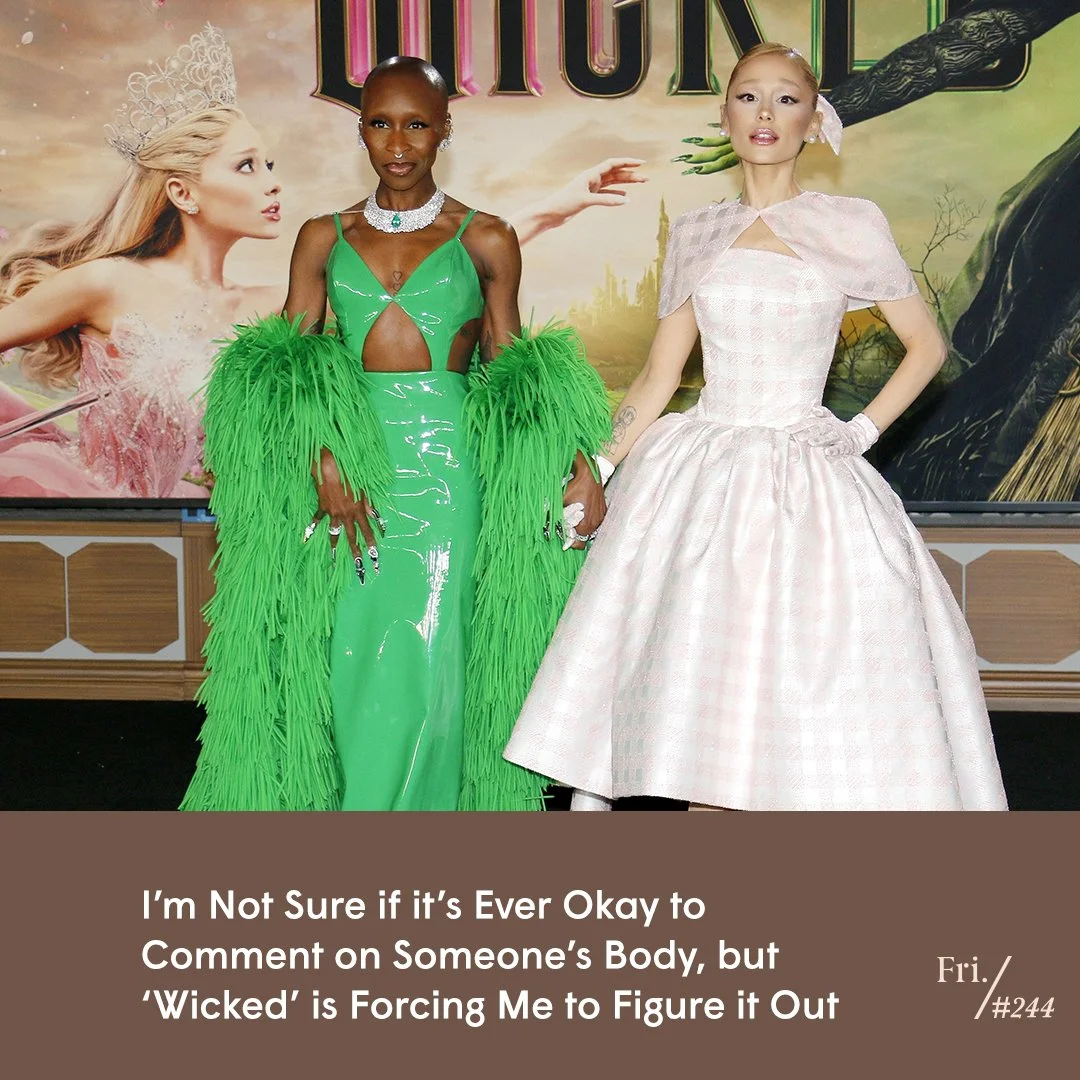

If you’ve seen recent photos of Grande and her Wicked: For Good co-stars, Cynthia Erivo and Michelle Yeoh, you know where this is going: it feels impossible to ignore such extreme weight loss, especially in the context of society’s enthusiastic return to thinness. So… what do we actually do? I don’t have a perfect answer. I don’t even think a perfect answer exists, honestly. But I do think it’s important to talk about what’s happening here.

There are good reasons why experts advise against speculating about eating disorders

It’s important to start by acknowledging that the experts are very clear: it’s not appropriate to comment on people’s bodies or question whether they have an eating disorder, even if you think you’re not judging and are instead simply raising concerns about their health. Last year, the press tour for the first Wicked movie sparked a similar discourse. At the time, Rebecca Boswell, a supervising psychologist at the Princeton Center for Eating Disorders at Penn Medicine Princeton Health, told Women’s Health magazine that, “we cannot tell who is healthy by looking at them—medical illness and psychiatric illness including eating disorders can occur across ages, genders, races/ethnicities, and body sizes. Public commentary on bodies reinforces the idea that physical appearance is the most important aspect of how a person is perceived and evaluated. This focus can lead to people devaluing their many other traits and roles.”

Even comments that aren’t intended as judgment can feel like it, which, in addition to being a source of psychological harm can also contribute to social stigma, and that only makes it harder to get help. Yes, Grande, Erivo and Yeoh likely aren’t going to see every specific post, but according to the National Eating Disorder Information Centre, “based on prevalence data from international research, at any given time, an estimated 908,000 to 1,900,000 people in Canada have symptoms sufficient for an eating disorder diagnosis,” so someone will.

For reference: https://t.co/jwqIal5KUb pic.twitter.com/f6EPIwHgzd

— Myy (@amusingmyy) November 19, 2025

It’s probably also a good idea to question the motivation behind some of the posts we’re seeing, especially those comparing these actors’ bodies before and after Wicked. Is that really about anyone’s well-being, and even if so, is that enough to counter the weirdness of analyzing someone’s body for social media engagement? Because the more time I’ve spent thinking about it this week, the more I think posting zoomed-in photos of Grande to look for lanugo is on the same spectrum as publishing photos of young women to highlight how poorly they adhere to the ultra-thin-is-in beauty standards of the day.

There’s also another factor at play here, which is that commenting about how ‘emaciated’ or ‘skeletal’ someone looks isn’t necessarily the deterrent we might want it to be. I’m sorry to be the one to introduce this to you if you haven’t already heard of it, but there’s an entire subset of the internet devoted to ‘pro-ana’ content, which is short for pro-anorexia and provides a space for people who have eating disorders to congregate virtually. Ostensibly, the purpose of these sites is to provide a non-judgmental space where people can connect with those who are going through similar experiences. Functionally, they often encourage eating disorders via “diatribes against medical and mental-health treatments, accompanied by photos of emaciated adolescents that convey a strange combination of starvation and sexuality. [Visitors to the site] share their particular obsessions: the space between the thighs, protruding ribcages, hipbones like boomerangs[. There’s also] disquieting discussion about how to improve and maintain eating disorders, including ways to curb the insistence of the body’s appetite,” as psychologist and eating disorder researcher Tom Wooldridge described them in a 2019 Aeon article. In that context, highlighting how dangerously thin someone looks is a compliment. (And no, pro-ana content and its slightly less scary sounding sister, thinspo, isn’t restricted to websites you can block with parental controls; it’s on all the social media platforms, especially TikTok, often hidden within seemingly innocuous posts about clean eating, fitness and wellness.)

It feels like we’re back in 2003, in all the worst ways

But here’s the thing. Even knowing all of that, it still doesn’t seem realistic to expect people to ignore that Grande, Erivo and Yeoh look drastically thinner than they did a year ago. And if I notice, you know other, more vulnerable people are noticing too. Not to be all ‘what about the children,’ but like… I deliberately curated my Instagram feed years ago so I’d see many different body types. It was a deliberate strategy, a way to unlearn the fatphobia I’d internalized as a child and teenager. (Which worked, P.S. I spent my 30s so much happier in my body than I was in my 20s and teens, at least in part because I saw so many different body types presented as beautiful, which kind of forced me to apply that logic to myself.) Now, so many of the body positive influencers I followed are on GLP-1s like Ozempic, the fashion brands that were slowly diversifying their runways seem to be done with all of that, and more and more celebrities are showing up on red carpets at early 2000s levels of thinness. If I can see the difference in my feeds—and feel a bit worried about what that’s doing to my own body image—do we really think kids and teens are somehow safe from internalizing those messages, knowingly or not?

@sedonaviolet Deja Fu*king Vu

♬ original sound - Sedona Violet

Because to be clear, what’s happening is bad. According to study published in the December 2023 issue of the Journal of Pediatrics, globally, the prevalence of eating disorders in the general population has more than doubled between 2000 and 2018, going from 3.4% to 7.8%. And researchers in the U.S. and Europe have both observed a “significant increase” in eating disorders in youth and adolescents, especially since the onset of COVID-19. In the U.S. in 2018, people under the age of 17 accounted for approximately 50,000 health visits related to eating disorders; by 2022, that number rose to just over 100,000, an increase of 107.4%. This is especially troubling since research shows people with eating disorders have higher mortality rates compared to other psychiatric disorders, with anorexia having the highest at 5%. The reasons for this increased prevalence obviously can’t be reduced to one simple factor, but it seems undeniable that what we’re seeing in media, and particularly social media, makes an impact. According to the U.S. National Eating Disorders Association, “studies have found that social media use, particularly engaging with appearance focused content that idealizes thin bodies, taking selfies and viewing and/or comparing oneself to images of celebrities, peers or family increase body dissatisfaction and can lead to disordered eating among both females and males.”

Here’s one example: Last year, a young Polish woman named Karolina Krzyzak died at a resort in Bali, the end result of a years-long battle with disordered eating that was absolutely exacerbated by her participation in an online community of ‘fruitarians,’ raw vegans who eat only fruit. According to a Cut article about Krzyzak published in September, “she fashioned herself after the influencers she followed on social media, posting flawlessly composed images of cinnamon-dusted blueberries and dragonfruit bowls. As she wasted away, her loyal followers cheered her on. ‘I truly believe that you have the right answers. You know what’s good for you even if right now seems like chaos,’ one wrote on a selfie she posted in 2023. ‘Nice neck and collarbones,’ a fan wrote on a photo she posted where her clavicle juts out of her skin. ‘It is so nice to see you so happy,’ another posted on a video of an Instagram Live she did last September. She would be dead less than three months later.”

And it’s not just young people, btw. A recent New York Times article followed several older women who are seeking treatment for eating disorders. Some have had these illnesses for decades, though for others the onset happened around menopause; either way, it’s tragic to see these women, who are in a life stage that we’re increasingly told will be characterized by confidence, acceptance and freedom, instead tormented by the reality of their bodies. Also, doctors are now seeing the long-term impacts of disordered eating on older bodies—not only are these women experiencing osteoporosis, arthritis, dental issues and heart disease, they’re also more medically fragile, and therefore not as equipped to recover from illness or surgery.

@lindsayfitzg Let’s hear those ideas boys.

♬ original sound - Lindsay FitzGerald

Maybe it’s time to accept that any real conversation about this will be nuanced, and therefore uncomfortable

I’ve been talking about Grande, Wicked and whether it’s okay to talk about these things in my group chats for days now. My friends are feminists, of many different backgrounds, with many different body types. Some have spent their careers as body positivity or body neutrality advocates, but not all. Still, almost everyone subscribes, to some degree at least, to the idea that we don’t talk about other people’s bodies. And yet, we’re all disturbed, not just because something looks amiss in these photos and videos of Grande in particular, but also because it feels like there’s a cone of silence surrounding them.

In so many ways this makes sense; we don’t typically talk about men’s bodies this way. When Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson recently lost a ton of weight for a role in the upcoming Benny Safdie project Lizard Music, there wasn’t as much of this hand-wringing tone (though there was some concern). And when Guardians of the Galaxy’s Dave Bautista basically body checked on LIVE with Kelly and Mark last year, it definitely didn’t spark a discourse like this one. (Body checking is the compulsive act of assessing your weight, shape, size and appearance, and is associated with body dysmorphic disorder and eating disorders.) Also, historically, conversations about women’s bodies have been harmful. And, I think there’s a linguistic thing going on, too. Somewhere along the way, the idea that we should never comment on people’s appearance has become intertwined with the right to bodily autonomy, with the reproductive justice rallying cry of “my body, my choice” now applied to any decision we make about our physical forms. For the most part, I think this is cool. We are all entitled to decide who gets to touch us, what kinds of food we want to eat or how we want to look. But not everything that happens with our bodies is a decision. Sometimes, something is wrong.

I recognize this is a hard one to navigate, which is why women’s magazines and entertainment publications have largely covered this story through the lens of bodily autonomy. These culture critics and columnists don’t seem to be willing, or capable, of making a distinction between body talk and raising a red flag—and I think there is a distinction. I truly believe smart, thoughtful adults should be able to understand the difference between mocking someone’s body and recognizing the signs that we are returning to an era of normalized disordered eating. For me, there’s an uncomfortable cognitive dissonance in pretending we’re not seeing what we so clearly are. Worse, the maxim that we ‘don’t talk about people’s bodies’ allows us to skip a complicated conversation under the veneer of progressiveness, something a friend calls the ‘ethical write-around.’

@fumptruck Influential people influence people. They are not infallible gods in a vacuum without any control or knowledge of how they impact other people. ##wicked##cynthiaerivo##arianagrande ♬ original sound - Gremlin 🍉

All of which is to say, while I agree that it’s inappropriate to speculate on someone’s diagnosis or post objectifying photos of their bodies, I feel pretty frustrated at the idea that we shouldn’t talk about the possibility that these celebrities are starving themselves to death, and especially that doing so would be tantamount to body shaming. In fact, I think we have to talk about it, even if it’s uncomfortable or imperfect. Lives may literally depend on it.

Thank you for reading this week’s newsletter! Still looking for intersectional pop culture analysis? Here are a few ways to get more Friday:

💫 Upgrade to a paid subscription to support independent, progressive lifestyle media, and to access member-only perks, including And Did You Hear About, a weekly list of Stacy’s best recommendations for what to read, watch, listen to and otherwise enjoy from around the web. (Note: paid subscribers can manage, update and cancel their subscriptions through Stripe.)

💫 Follow Friday on social media. We’re on Instagram, YouTube and (occasionally) TikTok.

💫 If you’d like to make a one-time donation toward the cost of creating Friday Things, you can donate through Ko-Fi.