“There Are So Many Real World Consequences That People Don’t Notice”

By Stacy Lee Kong

Image: Kristen Lopez

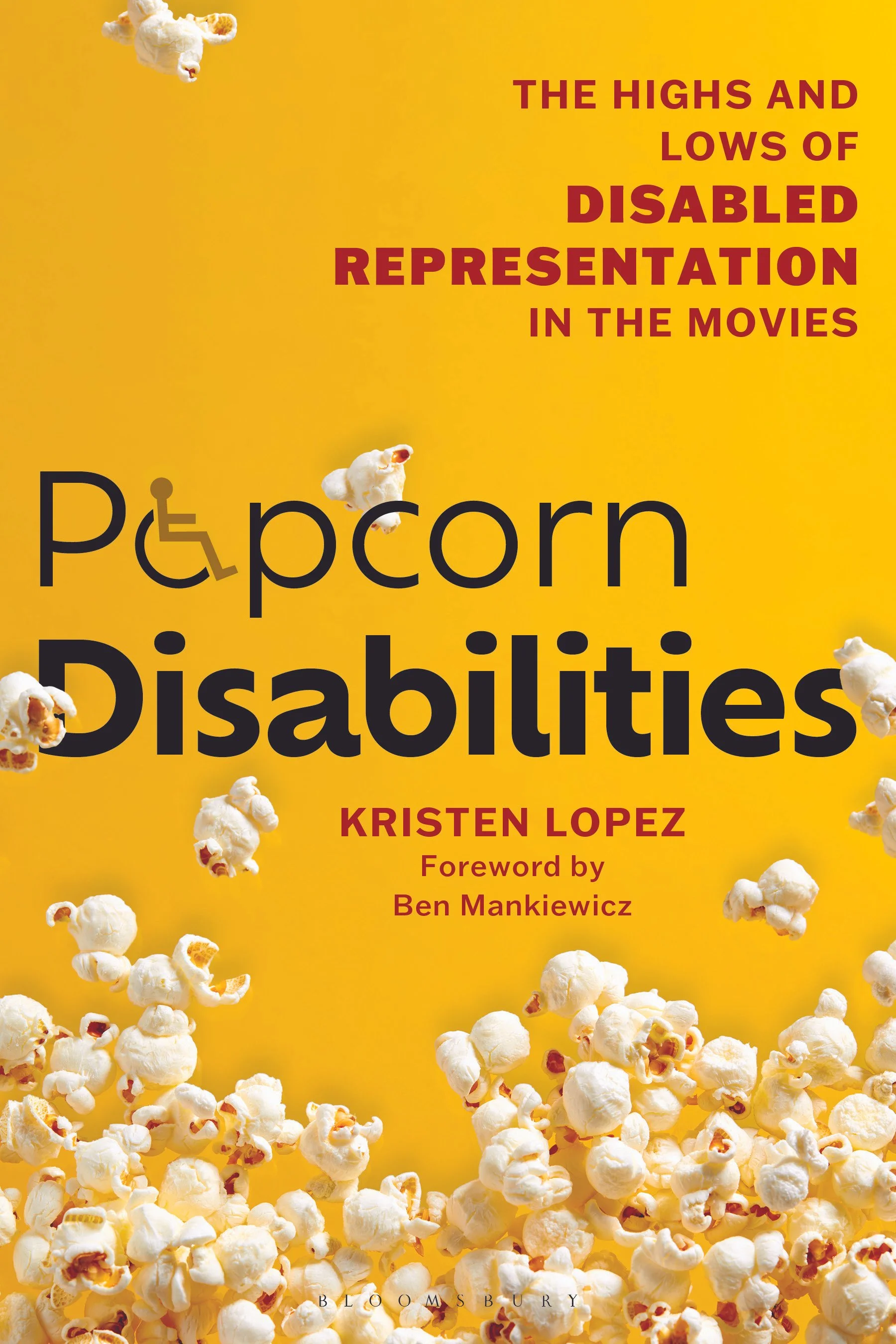

When I say I had a hard time editing down the transcript of my conversation with entertainment journalist and The Film Maven editor-in-chief Kristen Lopez, please know I really, really mean that. Late last year, we had a really great, and wide-ranging, conversation about her new book, Popcorn Disabilities: The Highs and Lows of Disabled Representation in the Movies. We basically said hello and immediately got into how Hollywood has historically portrayed disability and disabled people, if we’re actually seeing meaningful improvement and—very on-brand for both of us—why all of this matters. Read on for (a much shorter version, I promise!) our chat.

I think my favorite part of the book is that, as you talk about how disability has been portrayed in film throughout history, you’re also constantly circling back to what’s happening in the world culturally, politically, socially, even historically. Why did you want to connect what you saw on-screen with what was happening off-screen?

I always say films are a dialectic; they influence the culture and the culture influences the films. Dickens’ Tiny Tim had set this tone [of disabled people as] innocent, childlike characters, but from the 1920s into the 1930s, eugenics falls out of favour—because the Nazis co-opted it—and instead you get characters like Frankenstein’s monster, where the outer appearance may be scary but inside is this gentle giant who’s tragic and just wants to be loved. Then, once you hit 1932, Todd Browning’s film Freaks comes out. He really wanted to make this authentic portrayal of disability and the freak show circuit, which was slowly starting to come out of vogue, and MGM completely rejected it and turned it into a horror movie. It’s one of the films that is said to have ushered in the Hays Code, which dominated the latter half of the 1930s. All because we wanted to treat disabled people as people, you know? And then, in the ‘40s, after World War Two, you are getting a lot of disabled men returning home and movies have to, essentially, act as propaganda for that. You know, ‘Hire a disabled person!’ ‘Here’s what their lives are like—nothing’s different.’

Once Born on the Fourth of July comes out—in 1989, right around the time the ADA passes—you’re immediately seeing the effects of this post-disability landscape. So, there’s a lot more ramps integrated into things. I always laugh; in Forrest Gump, there’s a sequence where Forrest is at the top of this ramp, and Lieutenant Dan falls down the end of this ramp. The joke is like, ‘Oh, he crashed. Humour!’ But I think at this point in the movie, it’s the late ‘70s. That would not be a ramp! That would be stairs. But it was made in 1994. You can slowly see directors and creatives in the early ‘90s having to respond to this idea that disabled people are taken care of. So, I mean, movies have always been a reflection of what’s going on, and they always reflect the time period that they’re made in.

One of the things that really stuck out to me was how you wrote about gendered portrayals of disability, and specifically the idea that, with men specifically, disability can ‘spread’ through sexual violence. I immediately saw a very clear parallel to race there.

Oh yeah, they’re analogous. They’re not the same, because there’s a whole deep history with racism that is totally different than that of disability, but we’re all striving for the same thing, which is accurate representation in entertainment. And I think the ways that we’ve seen Black representation in film change and transform into what it is today kind of creates a ladder, or a foundation, for how we can do disability. Although the distinction is, we know race is a personal identifier. We see it as such. It’s as ingrained in you as your gender, as your sexual orientation. But there are still a lot of people that couch disability as a medical issue, as opposed to a personal identity. So, I think that the problem is, Hollywood sees gender, sexuality and race as personal identifiers and thinks, ‘We have to get with the times and actually be authentic.’ But people still see disability as a temporary medical issue. They think, ‘You’re not your disability, you’re beyond that.’ I think there’s such a start-stop with disability and film.

What do you mean by disability being ‘start-stop’ in Hollywood?

So, we usually get one big movie every couple of years, and people assume that’s going to be the film that’s going to fix everything. We saw it with Born on the Fourth of July. When Coda came out in 2021 and won Best Picture, people were like, ‘Finally, this is the movie.’ But we’re five years out from Coda winning Best Picture, and according to Annenberg, the needle has not moved on disability representation. It’s still the same 2.4% that it’s been since 2015. I think the community banks everything on one movie, and then nothing happens. Next year, we have a Judy Heumann biopic, and I’m just going to be the rain cloud that’s like, ‘I’m so sick of hearing about The One.’ I want more than one. I don’t know, can we maybe get two? I’d probably pass out if we got five.

There’s also something to how disability is presented, too, right? What are the ‘fails’ that studios perpetuate over and over again, that you want people to notice and understand as ableist?

I think the big one is what I call the ‘able-bodied buffer,’ which is the idea that you have to show an able-bodied person. You show the disabled person disabled late in life, so the audience gets to see a period where they’re able-bodied and can identify with them. To go along with that, you often get a movie where an able-bodied character is the true star of the film. Me Before You is not necessarily Sam Claflin’s story; Emilia Clark is the star. This happens a lot, and once you start noticing it, you can’t unsee it. The stories often become about the able-bodied character, and how they are changed for good by noticing the disabled person.

If you see anybody that’s in a hospital collapsing wheelchair, that is inauthentic. No wheelchair user worth their salt is sitting in that damn thing all day. They are impossible to wheel, they have no support for your back. If you’re not seeing somebody in a custom chair, nobody did their research.

I think, too, with caregivers in movies, there’s often the question of whether they’re a caregiver or a sex worker. This happens a lot more frequently than it should, especially if the inter-abled relationship is disabled man and abled woman. You usually don’t get that with disabled women and abled men, mostly because we don’t see those stories an awful lot.

The other thing is there’s no intersectionality. If you get a disabled person of color, you can only deal with one thing, so you can either deal with ableism or you can deal with racism, but you can’t have them both. I think this is a really, really problematic part, because you can’t ignore both.

Right, because in life, you do have to deal with both all the time. It’s a real flattening of disabled people’s experiences. Are there recent or upcoming projects that are counterpoints to this type of storytelling, though?

The Judy Heumann biopic is going to be the big thing. It’s directed by Sian Heder, who did Coda. He’s casting authentically. I’ve heard that there were disabled people in the screenwriting process, so that’s been really great. But I think for the most part, it’s disabled people creating their own stuff. Reid Davenport just did a documentary this year called Life After, a brilliant documentary about the right-to-die laws in Canada, and the growing movement that is happening in the U.S., and it’s fantastic. So, I mean, we’re the ones that are still kind of doing the damn thing. That’s a problem.

And you look at certain movies… I keep griping about this movie, but you know the Neil Diamond movie with Hugh Jackman and Kate Hudson, Song Sung Blue? Nobody except me is talking about how ableist that movie is. Most people don’t even know there’s a disability component in that film.

I did not know there was a disability component.

Yeah, the Kate Hudson character gets hit by a car and loses a leg. It had been a minute since I’d seen a really old fashioned, stereotypical character who is—as I call it in the book—a ‘bitter cripple.’ She’s this drugged out woman bemoaning how she misses her leg. She has a dream sequence where she’s performing with both legs while she’s in the middle of a Percodan haze on her front lawn. Her husband commits her to rehab against her will to save her. It’s a lot of overwrought disabled trope-iness. But this is all based on a true story, which is how creatives commonly get around disability critiques: ‘Well, this really happened, okay?’

There was a movie that came out a couple years ago that that ended with the disabled characters in the afterlife, where they were ‘whole’ because their limbs are back. I went on social media and I said, “Well, it’s really, really ableist.” I got a phone call from the film’s reps, who were like, “Why would you say that?” That creative team clearly doesn’t know that the history of disabled people is the history of death being [positioned as a] great cure all for us. There are really dangerous implications to that [creative choice]. But I just don’t think a lot of people know what ableism is. It’s a relatively new ‘ism’ in the grand scheme of things. They live in this kind of bubble of ignorance, where they’re like, ‘Well, we don’t know these things. We have plausible deniability.’

I definitely still have moments like, ‘Oh shit. That’s what’s happening here.’ So there’s an ongoing process of unlearning and unpacking ableism, absolutely. But the existence of ableism is not a hard concept to wrap your head around!

I tell people all the time, and I say it in the intro to the book, that my goal with is not to make you feel like you’re a horrible person because you love Forrest Gump or any other movie. The biggest thing I wanted to illustrate with the book is that there’s a generation of disabled people that have grown up with these movies that have made them feel a way about themselves. As a disabled teen girl, I didn’t have anybody that looked like me—and if somebody like Molly Ringwald couldn’t get the guy and she was beautiful and ambulatory, then what the hell shot do I have? When you don’t see those rites of passage in film, you just assume they don’t exist. And for me, especially, women who are wheelchair users are often 5’6” and they’re sitting in a chair. They’re proportionate. They have no visible depictions of their disability. And again, that always made me say, ‘Well, I can’t pass. So if I can’t pass, what does that mean?’

So, I think that the goal with the book has always been to have able people read it and be like, Oh, okay, I should be asking why that wheelchair looks like it’s from a hospital, and I should be asking why there’s always an able-bodied person that’s actually telling the story, as opposed to the disabled person telling the story. Why are all disabled people white guys? I think once people start thinking about that, then we start seeing the change, because it puts it on their radar where it hasn’t been before.

Because much like other types of oppression, you need people who aren’t experiencing it to put pressure on these various systems, right? I’m really curious to hear more about what it’s like for you to watch depictions of disabled women on-screen, rare as they are.

The threat of sexual violence in a lot of these movies is very high. We know that the stats about sexual violence for disabled women in America are very high, specifically from people that they know, so to watch something like Johnny Belinda [a 1948 movie about a deaf-mute young woman, Belinda, who is raped by a man who patronizes her family’s farm] is disturbing. It’s very, very disturbing. Or even The Shape of Water, where you are watching harassment and sexual violence. It’s a flawed movie for sure, but I always applaud Guillermo del Toro for showing what sexual harassment against disabled women looks like. When Michael Shannon’s character tells Sally Hawkins’ character, “I don’t mind that you are deaf,” that is the most terrifying sentence because it’s supposed to be presented as a kindness. I recounted my own story in the book, and I’ve literally had somebody sit me down and say, “You know, the harassment you’re experiencing… isn’t it great that this person doesn’t see your disability, though?” I think there’s still this weird, backward mentality that disabled people, especially disabled women, are going to have a really hard time finding partners.

it almost feels like the second, unspoken part of that is, ‘so be grateful for the attention.’

Yes. And I think that the history of disability and film is one of ‘we just need to be grateful.’ We see that outside of film: Be thankful that you have Coda. And you see that in the films where you have characters that are just so happy to be alive—you know, the Tiny Tims. I’m beyond the gratitude at this point. I just want the bare minimum. I don’t want to be harassed. I want to be able to access a building. I would like to have a home that I can afford.

Not to continue to shit on Song Sung Blue, but Kate Hudson got a Golden Globe nomination for this performance, which is stunning and brave and resilient. Because we love us a resilient disabled woman, who’s pretty and comes out the other side and nobody minds that she’s rocking one leg—which you never see because she wears long dresses all the time. It’s very frustrating, because there are so many real world consequences that people don’t notice.

Popcorn Disabilities: The Highs and Lows of Disabled Representation in the Movies is on sale now. You can also read more of Kristen’s work at The Film Maven, and follow her on Instagram and X.

Thank you for reading this week’s newsletter! Still looking for intersectional pop culture analysis? Here are a few ways to get more Friday:

💫 Upgrade to a paid subscription to support independent, progressive lifestyle media, and to access member-only perks, including And Did You Hear About, a weekly list of Stacy’s best recommendations for what to read, watch, listen to and otherwise enjoy from around the web. (Note: paid subscribers can manage, update and cancel their subscriptions through Stripe.)

💫 Follow Friday on social media. We’re on Instagram, YouTube and (occasionally) TikTok.

💫 If you’d like to make a one-time donation toward the cost of creating Friday Things, you can donate through Ko-Fi.